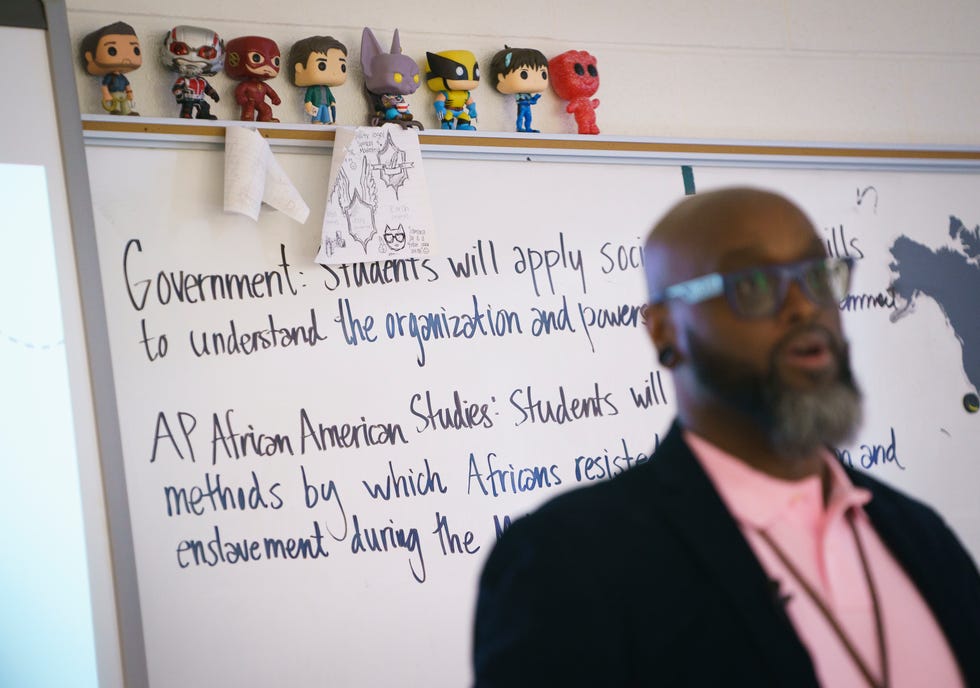

LORTON, Virginia – Sean Miller quiets the stereo blasting Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” and begins his lessons for the day, a journey through centuries with improvisational stops along the way.

He kicks off with a discussion on Black joy. Today’s focus: Olympic gymnast and fellow Virginian Gabby Douglas. Then his roughly two dozen students move on to another topic: Black History Month. Has the yearly event outlived its relevance? Miller asks after playing a video clip about the month’s origins. No, some say. A teen proposes legislation to mandate its observance.

Next the discussion veers to distinctions between “slave” and “enslaved person.” One emphasizes a person’s status, the other their humanity. Then students analyze sketches of captives from the 1839 Amistad rebellion. By the time class wraps up, Miller has drifted through the good and bad referenced in the Al Green anthem, stringing together topics like a chord progression. “Finding the triumph amid all the challenges and tragedies requires a little bit of creativity,” he later explains.

Welcome to Advanced Placement African American Studies. The course – still in pilot mode – has drawn praise from students nationwide but sparked restrictions in Florida and Arkansas amid concerns from conservatives that the curriculum is leftist propaganda and makes white children feel bad about themselves.

The course has the rigor of a college-level offering and the interdisciplinary scope of an ethnic studies seminar, comprising four units that extend from ancient African civilizations to modern-day movements. In mid-May, about 13,000 students at 700 schools in 42 states and Washington, D.C., will be eligible to take the AP African American Studies test. High scores could earn students credit at more than 300 colleges that have indicated they’ll grant it.

While the stakes and the difficulty level are high, students say the material is resonant and accessible. Caury Crusoe, 17, said the class often feels like “an hour-and-a-half conversation.” In interviews with USA TODAY, students and educators described the course as transformational. Taking it improved their self-esteem and gave them a newfound pride in their ancestors, many Black teens said. Others emphasized the illuminating content and their deeper appreciation for what humans have in common versus what they don’t.

The immense demand from teens – especially Black youth, who participate in AP classes at lower rates than their white and Asian peers – suggests many more U.S. schools will pick up the course once it goes live this fall. The AP class could continue to face headwinds in the coming years as proposed bans targeting critical race theory (CRT) and diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) turn up on legislative agendas.

The College Board declined to say which schools are offering the class. But states, districts, universities and local reporters helped USA TODAY identify roughly 370 campuses based in nearly 200 school districts that are offering the class, accounting for more than half the schools piloting it. Some of these campuses, including the only Florida institution piloting it, are private schools.

A large majority of the schools and districts offering AP African American Studies are in communities that voted for President Joe Biden in 2020, USA TODAY found. Taken together, those districts also had a greater percentage of Black high school students than the national average.

A separate USA TODAY analysis of email correspondence from education officials in some red states revealed staffers’ hesitancy to embrace the course because of the optics.

“There’s always a certain amount of fear and anxiety and backlash that’s associated with these efforts,” said Michael Hines, a Stanford education historian who studies activism in African American communities. Hines foresees an ongoing battle over this course as part of a “recurring cycle.”

AP African American Studies sparks concerns over critical race theory

The launch of AP African American Studies is a watershed moment that says “African American history – the African diaspora – it matters,” said Thomas Tucker, the chief equity officer with Kentucky’s education department. “My hope is that historians will look back on this period to say we’re finally at a point of helping Americans … understand the beautiful complexity, the beautiful tapestry, of the long, long history of the African people.”

Critics often portray AP African American Studies as a course fixated on division and suffering. That perception nearly deterred two of Miller’s students from signing up. Renee Prox, 17, wondered whether college admissions officers would look down on her for taking it because of the politics. “I wasn’t sure if it would look bad on my transcript,” said the senior, who is Black.

One of Prox’s few white classmates, Abigail Plageman, also debated whether to take the course. Plageman said her parents were skeptical because of what they’d heard in the news about CRT.

Claims the course would delve into CRT, a graduate-level theory that examines how racism permeates societies and systems, were widespread as the framework underwent revisions.

Florida’s education department in January 2023 banned the course because it lacked “educational value,” and Gov. Ron DeSantis described a draft framework as a “political agenda” that sought to “shoehorn” radical progressive concepts into history instruction. A subsequent version excluded many themes DeSantis called out, prompting critiques from course advocates who accused the College Board of whitewashing content educators had extensively workshopped. Experts last summer convened for another round of edits that led to a version released in December. Some controversial topics – like intersectionality – were reintroduced, while others – like the Black Lives Matter movement – remain optional.

After DeSantis banned the course, Arkansas’s education department restricted it, too, and several red states promised to review it. (Ultimately, half a dozen Arkansas campuses opted to pilot it, but, because of the state’s stance, participating students cannot earn credit toward graduation. However, now that the framework has been updated, Arkansas students may be able to earn credit next year under the state’s graduation requirements, a department spokesperson told USA TODAY.)

Explained:Gov. Ron DeSantis’ feud with the College Board over AP African American Studies

Email correspondence obtained by USA TODAY shows some employees in red states last year were questioning what to do about the class following DeSantis’s and others’ critiques.

“I am a bit concerned about this course,” wrote Davonne Eldredge, North Dakota’s assistant director of academic support, in a January 2023 email to a superior about a College Board request that the state adopt it. “This is the course that has been in the national news due to critical race theory concerns brought forth in Florida. … Given the hot item critical race is within ND, I’m not sure how to proceed with this one. My gut says to hold off until the changes are made.” The state never formally reviewed the course because no school asked to pilot it, a spokesperson said.

In Virginia, another state where officials vowed to review the curriculum, media coverage of the controversy seemingly prompted decision-makers to waffle over their messaging. The state education department concluded that the course complied with Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s anti-CRT executive order and drafted a related statement to share its conclusion with the public, email records show. The draft included a suggestion that more edits be made to the course, but staffers worried that language would prompt inquiries from reporters.

South County High, where Miller teaches, is one of about 16 schools in Virginia piloting the class this school year. In that state, AP African American Studies will remain an elective rather than a social studies course that counts toward graduation.

Despite the revisions, some critics who closely follow the course’s development remain concerned.

Michael Gonzalez, a fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation, said CRT and the activist mindset of the Black Lives Matter movement remain prominent in the latest framework even though these topics have been left out or made optional. As long as discussions of systemic racism are included, it’s still grounded in CRT, in his view. The word “oppression,” he stressed, is mentioned 19 times.

In an interview with USA TODAY, Gonzalez and his colleague, Jonathan Butcher, agreed it’s important to teach about the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow. But viewing all history through the lens of racism and oppression, they said, is misleading and incendiary.

“We want young people to believe that the American dream belongs to them … that they do have a future,” said Butcher, an education policy research fellow at Heritage. “If you, instead, give young people something that they need to resist, to look down upon, you’re robbing them of the chance of having something to live up to.”

Seeing Black history ‘for more than just the bad’

Over several months and during two visits to Miller’s classroom, students told USA TODAY the course broadens their knowledge and instills hope. Plageman, the white student whose parents were skeptical about the course, said she’s politically centrist and feels the lessons haven’t changed her viewpoints. Rather, they’ve expanded what she knows about the U.S. AP African American Studies is not CRT, she said, but “just another social studies class that’s different from what I’ve learned before.”

Prox, the Black student concerned about having the course on her transcript, explained she hasn’t looked back since she signed up. “It’s way more than what it’s been painted out to be,” she said. “It’s about how the African diaspora has grown and how we started and it’s just a really good representation of Black people.”

“We were oblivious to how the story of an African past is a glorious one. It’s not just a reshaping of the narrative. It is an introduction of a narrative that, for so many of us, simply did not exist.”

Teresa Reed, a dean and music professor at the University of Louisville, who serves on the course’s development committee

Black history is under attack:From AP African American Studies to ‘Ruby Bridges’

Crusoe, who described the course as a long conversation, said the knowledge she’s gained has made her more ambitious and proud. It inspired her to branch beyond her goal of studying business to explore a humanities discipline with an emphasis on social justice when she attends North Carolina A&T, a historically Black college in Greensboro, next fall. She regularly shares tidbits from class with her mom and is president of her school’s Black Student Alliance. “I’m not a big history person, but (Miller) makes me want to talk about it,” she said.

Her favorite part, beyond Miller’s relaxed teaching style, has been learning about the strength of her ancestors. About the ancient African civilizations with legacies far more expansive than she ever knew. About the modern Black heroes whose art touches millions. About the everyday Black people, like her parents and herself, fulfilling the American dream. “People just don’t really see Black history for more than just the bad,” she said.

The Heritage scholars said a better strategy for teaching about African American experiences would be to broaden U.S. history education. That way, the history of Black Americans could be woven together with other groups. “African American history is my history,” Gonzalez said.

Students and educators told USA TODAY there’s a reason to separate this curriculum: U.S. history classes seldom scrape past the surface of African Americans’ role in the narrative, beyond slavery and civil rights.

It’s groundbreaking for an African American studies course like this to come together on a national scale, endorsed by the College Board. “It feels like a gap is being filled in my own psyche,” said Teresa Reed, a dean and music professor at the University of Louisville who serves on the course’s development committee.

Growing up in predominantly Black Gary, Indiana, in the 1960s and 70s, Reed didn’t learn much about the contributions of her ancestors or the pre-slavery chapters of their story.

“We were oblivious to how the story of an African past is a glorious one,” she said. That’s what makes this course so novel: “It’s not just a reshaping of the narrative. It is an introduction of a narrative that, for so many of us, simply did not exist.”

‘These are people who persevered’

The interdisciplinary, meandering nature of the South County High classes USA TODAY observed this spring is precisely what developers envisioned when they designed the course. The idea is for students to find connections between the past and present – between the Amistad rebellion and Gabby Douglas setting Olympic records.

Miller, a former marketing professional who chairs the high school’s social studies department, infuses his lessons with guidance on developing real-world skills. During a March class, students broke into groups to plan a podcast project. The final product, Miller told them, should be a neatly structured, professional-quality episode that touches on several topics of their choice from the curriculum. Their grade would count as their test score for the unit.

The classroom buzzed as the teens deliberated how to tackle this assignment. Crusoe and her partner designed logos and debated which to use – an animated ear against the word “Black” repeated in rows or a woman in 1950s attire with a TV as a head entitled “Shades of History”? Across the room, a boy scanned C-SPAN for good clips. In the back, three students discussed themes they’d highlight: Black music, fashion, literature and media representation.

Miller, who wears gauges in his ears and produces music in his spare time, peppers his lessons with a mix of banter, sarcasm and big words. Students fist-bump him on their way in and out. His mantra is simple: “Keep the rigor high, keep the expectations high. But create memories and keep it engaging.” Slavery, lynching and segregation are crucial elements of the African American experience, but Miller frames the discussion around resilience rather than bitterness or shame.

He strives to frame his instruction around “victories over victimization,” he said that March day. Wearing a “Built by Black History” T-shirt, he noted, “There were some dark days, but there were also some very positive days in response.”

“I want them to walk out the door and say, ‘Wow, these are people who persevered.’”

Contributing: Doug Caruso, data editor at USA TODAY, analyzed demographic and political trends across districts we identified were piloting AP African American Studies this school year.

Also contributing: Lily Altavena, Detroit Free Press; Caroline Beck, Indianapolis Star; Jillian Ellison, Journal & Courier; Samantha Hernandez, Des Moines Register; Kelly Lyell, the Coloradoan; Madeleine Parrish, Arizona Republic.