Officials say striking young doctors risk being punished if they don't return to work by the end of February.

The South Korean government has given striking young doctors four days to return to work and warned them that if they do not return by the deadline, they could be prosecuted and have their medical licenses suspended.

Monday's ultimatum came as about 9,000 medical trainees and residents walked off the job in protest of government plans to increase medical school admissions by about 65 percent.

The shutdown, which began last week, has severely affected hospital operations, with many surgeries and other treatments canceled.

Safety Minister Lee Sang-min said the strike had increased chaos at hospitals and that emergency services had reached a “dangerous situation.”

“Given the gravity of the situation, the government makes a final plea,” he said.

“If you return to the hospital from which you were discharged by February 29, you will not be held responsible for what has already happened,” he said. “Remember, your voice is heard loudest and most effectively when you are close to your patients.”

Government officials say more doctors are needed to cope with South Korea's rapidly aging population. Currently, the country's doctor-to-patient ratio is among the lowest in the developed world.

Young doctors protesting say the government should first address pay and working conditions before trying to increase the number of doctors.

Vice Health Minister Park Min-soo said those who do not return to work by the end of February will have their medical licenses suspended for at least three months.

He said he could also face further legal action, including an investigation and possible prosecution.

Under South Korea's medical law, the government can order doctors and other medical personnel to return to work if it determines there is a serious risk to public health.

Failure to comply with such orders could result in up to three years in prison or a fine of 30 million won ($22,480), as well as revocation of medical license.

There are approximately 13,000 medical interns and residents in South Korea, most of whom work or undergo training at 100 hospitals. They typically assist senior doctors during surgeries and attend to hospitalized patients.

They make up about 30 to 40 percent of all physicians at some major hospitals.

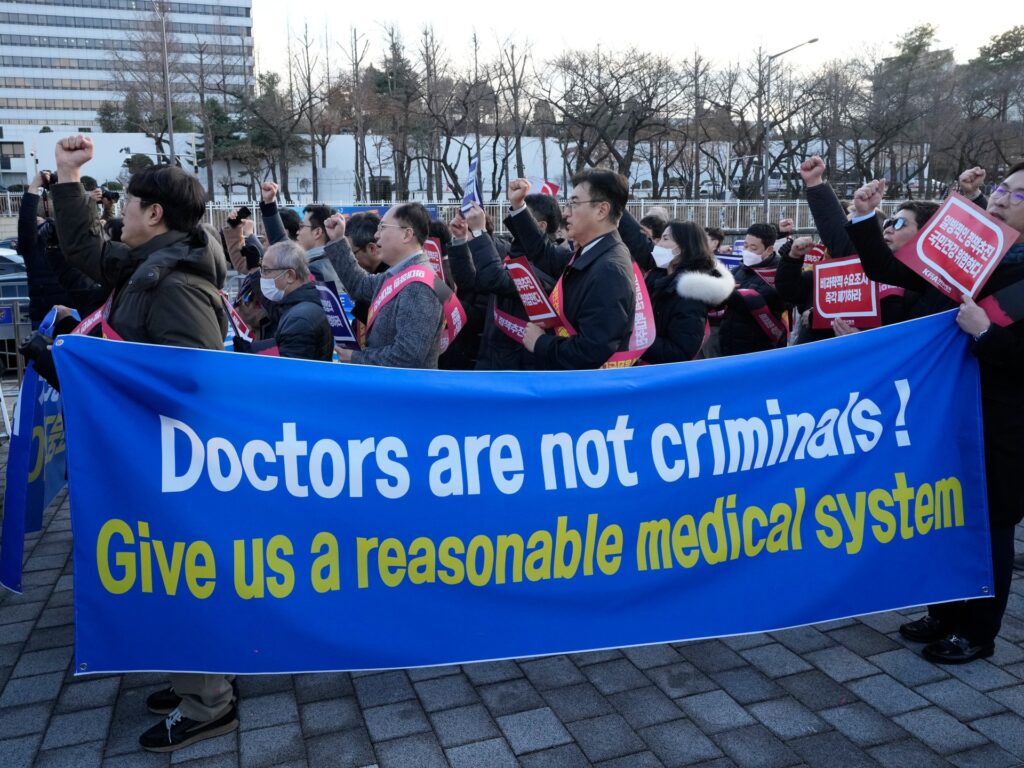

The Korean Medical Association, which represents about 140,000 doctors in South Korea, says it supports the striking doctors, but has not decided whether to join the strike by trainee doctors.

Senior doctors held a series of rallies to express their opposition to the government's plans.

Earlier this month, the government announced that universities will increase the number of medical students by 2,000 from next year, up from the current 3,058. The government aims to increase the number of doctors by up to 10,000 by 2035.

According to public surveys, about 80% of South Koreans support the government's plan.

Critics suspect that doctors, some of South Korea's highest-paid professions, are opposed to the hiring plan due to concerns about increased competition and lower incomes.

The striking doctors said they feared that in the face of increased competition, doctors would over-treat and burden public healthcare costs.