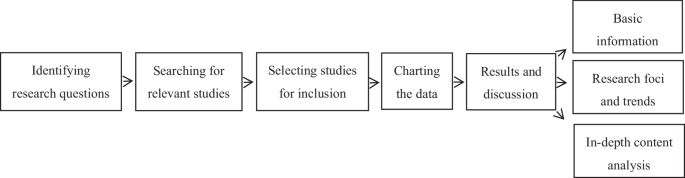

In accordance with the fifth stage of Arksey and O’Malley’s framework for a scoping review, the findings from the 233 included studies are summarized and discussed in the following three sections. Section 4.1 summarizes basic information regarding the included studies; section 4.2 presents a holistic analysis of the research foci and trends over time using keyword clustering analysis and keyword burst analysis; and section 4.3 offers an in-depth content analysis focusing on the categorization of the included studies and discussion of the major findings.

Basic information on the included studies

Distribution by year of publication

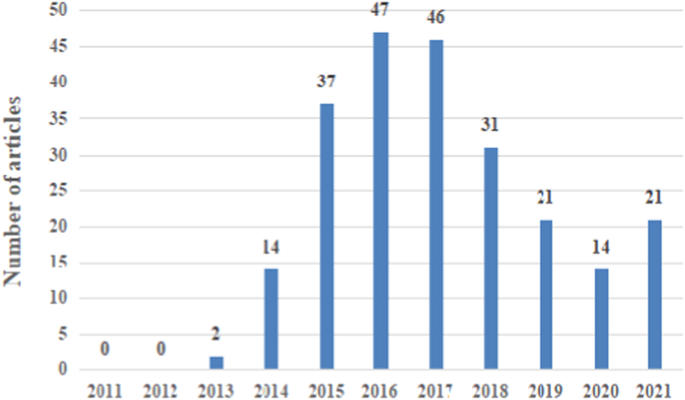

As Fig. 3 shows, the first studies on FCs in the field of FLT in China emerged in 2013. The number of such studies began to steadily increase and reached a peak in 2016 and 2017. Although there was some decrease after that, the FC model has continued to attract research attention, in line with global trends. According to Akçayir and Akçayir’s (2018) review of the literature on FCs published in Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) journals as of 31 December 2016, the first article about the FC was published in 2000, but the second was not published until more than a decade later, in 2012; 2013 was also the year that FC studies became popular among scholars. A possible explanation for this increase in interest is the growing availability of internet technologies and the popularity of online learning platforms, such as MOOCs and SPOCs (Small Private Online Courses), along with the view of the FC as a promising model that can open doors to new approaches in higher education in the new century.

Number of articles published by year.

Distribution by foreign language

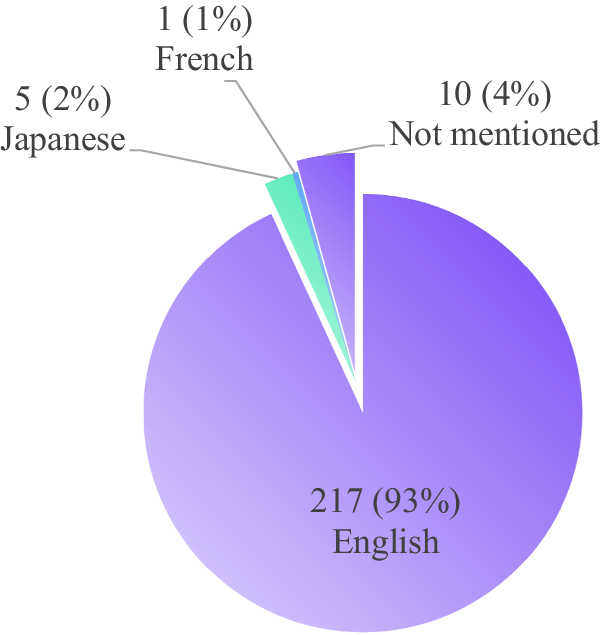

Figure 4 shows the distribution of foreign languages discussed in the FC literature. The FC model was mainly implemented in EFL teaching (93%), which reflects the dominance of English in FLT in Chinese higher education. Only five articles discussed the use of FC models in Japanese teaching, while one article was related to French teaching. Ten non-empirical studies (4%) reported the feasibility of FC models in FLT without mentioning a specific foreign language.

Distribution by foreign language type.

Research methods of the included studies

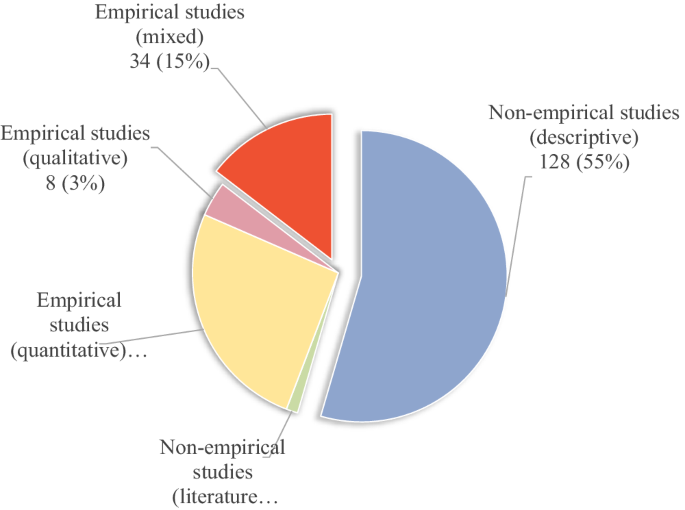

Figure 5 shows a breakdown of the methodologies adopted by the studies included in our review. Among the 131 non-empirical studies, three were literature reviews, while the remaining 128 (55%) were descriptive studies based on the introduction of the FC model, including descriptions of its strengths and associated challenges and discussions of its design and implementation in FLT.

Methodological paradigms.

Of the 102 empirical studies, 60 (26%) used quantitative methods for data collection, eight (3%) used qualitative methods, and 34 (15%) used mixed methods. It is interesting to note that although quantitative methods are more common in FC studies, seven of the top ten most-cited empirical studies (as listed above in Table 4) used mixed methods. A potential reason may be that research findings collected with triangulation from various data sources or methods are seen as more reliable and valid and, hence, more accepted by scholars.

A breakdown of the data collection approaches used in the 102 reviewed empirical studies is displayed in Table 5. It is important to note that most studies used more than one instrument, and therefore, it is possible for percentages to add up to more than 100%. The survey, as a convenient, cost-effective, and reliable research method, was the tool most frequently used to gain a comprehensive picture of the attitudes and characteristics of a large group of learners. Surveys were used in 79 of the 102 studies—73 times with learners and six times with teachers—to explore students’ learning experiences, attitudes, and emotions, as well as teachers’ opinions. Some studies used paper-based surveys, while others used online ones. Interviews with learners were used in 33 studies to provide in-depth information; one study used interviews with teachers. Surveys and interviews were combined in 24 studies to obtain both quantitative and qualitative data. Other research approaches included comparing the test scores between experimental and control groups (used in 25 studies) or using the results of course assessments (17 studies) to investigate the effects of the FC on academic performance. Learners’ self-reports (9 studies) were also used to capture the effects of the FC on learners’ experience and cognitive changes that could not be obtained in other ways, while one study used a case study for a similar purpose. Teachers’ class observations and reflections were used in eight studies to evaluate students’ engagement, interaction, activities, and learning performance.

Holistic analysis of the research foci and the changing trends of the included studies

A holistic analysis of the research foci in studies of FCs in China was conducted using CiteSpace5.8.R3, a software developed by Chaomei Chen (http://cluster.cis.drexel.edu/~cchen/citespace/, accessed on 20 February 2022), to conduct a visual analysis of the literature. This software can help conduct co-citation analysis, keyword co-occurrence analysis, keyword clustering analysis, keyword burst analysis, and social network analysis (Chen, 2016). In this study, keyword clustering analysis and keyword burst analysis were chosen to capture important themes and reveal changing trends in FC research.

Keyword clustering analysis primarily serves to identify core topics in a corpus. Figure 6 presents a graph of the top ten keyword clusters identified in the included studies. In this graph, the lower the ID number of a given cluster, the more keywords are in that cluster. As shown in the top left corner of Fig. 6, the value of modularity q is 0.8122, which is greater than the critical value of 0.3, indicating that the clustering effect is good; the mean silhouette value is 0.9412, which is >0.5, indicating that the clustering results are significant and can accurately represent hot spots and topics in FC research (Hu and Song, 2021). The top ten keyword clusters include #0翻转课堂 (flipped classroom), #1大学英语 (college English), #2 MOOC, #3教学模式 (teaching model), #4元认知 (metacognition), #5微课 (micro lecture), #6微课设计 (micro lecture design), #7英语教学 (English teaching), #8 SPOC, and #9 POA (production-oriented approach).

The graph of the top ten keyword clusters.

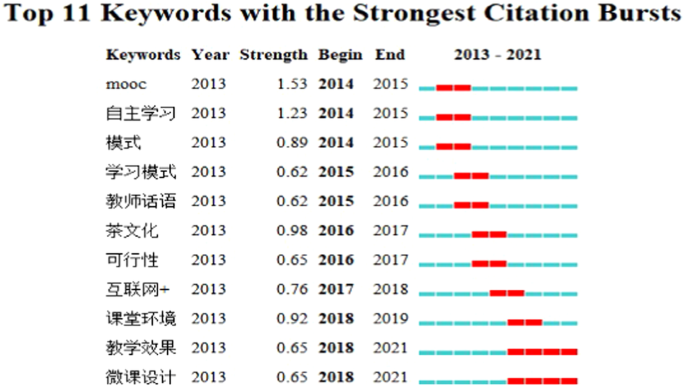

Keyword burst analysis is used to showcase the changes in keyword frequencies over a given period of time. By analyzing the rise and decline of keywords, and in particular, the years in which some keywords suddenly become significantly more prevalent (“burst”), we can identify emerging trends in the evolution of FC research. Figure 7 displays the 11 keywords with the strongest citation bursts. We can roughly divide the evolution of FC research documented in Fig. 7 into two periods. The first period (2014 to 2017) focused on the introduction of the new model and the analysis of its feasibility in FLT. The keywords that underwent bursts in this period included “MOOC”, “自主学习” (independent learning), “模式” (model), “学习模式” (learning model), “教师话语” (teacher discourse), “茶文化” (tea culture), and “可行性” (feasibility). The reason for the appearance of the keyword “tea culture” lies in the fact that three articles discussing the use of FCs in teaching tea culture in an EFL environment were published in the same journal, entitled Tea in Fujian, during this period. The second period (2018–2021) focused on the investigation of the effect of FCs and the design of micro lectures. Keywords undergoing bursts during this period included “互联网+” (internet plus), “课堂环境” (classroom environment), “教学效果” (teaching effect), and “微课设计” (micro lecture design). The latter two topics (“teaching effect” and “micro lecture design”) may continue to be prevalent in the coming years.

Top 11 keywords with the strongest citation bursts.

In-depth content analysis of the included studies

Along with the findings from the keyword clustering analysis and keyword burst analysis, an open coding system was created to categorize the research topics and contents of the 233 articles for in-depth analysis. Non-empirical and empirical studies were classified further into detailed sub-categories based on research foci and findings. It is important to note that some studies reported more than one research focus. For such studies, more than one sub-category or more than one code was applied; therefore, it is possible for percentages to add up to more than 100%. The findings for each category are discussed in detail in the following sections.

Non-empirical studies

The 131 non-empirical studies can be roughly divided into two categories, as shown in Table 6. The first category, literature reviews, has no sub-categories. The second, descriptive studies, includes discussions of how to use FCs in FLT; descriptions of the process of implementing the FC in FLT; and comparisons between FCs and traditional classes or comparisons of FCs in Chinese and American educational contexts.

The sub-categories of “introduction and discussion” and “introduction and description” in Table 6 comprise 91.6% of the non-empirical studies included in our review. The difference between them lies in that the former is based on the introduction of the FC literature, while the latter is based both on the introduction of the FC literature and exploration of researchers’ teaching experience; the latter might have become qualitative studies if researchers had gone further in providing systematic methods of collecting information or an analysis of the impact of FCs.

Empirical studies

The 102 empirical studies were divided into four categories based on the domain of their reported findings: the effect of FCs on learners; learners’ satisfaction with FCs; factors influencing FCs; or other research foci. Each group was further classified into more detailed sub-categories.

Effect of FCs on learners

Studies on the effect of FCs on learners were divided into two types, as presented in Table 7: those concerned with the direct effect of FCs on learning performance and those exploring the indirect effect on learners’ perceptions. Eight codes were applied to categorize the direct effect of FCs on learning performance, which was usually evaluated through test scores; 14 codes were used to categorize the indirect effect of FCs on learners’ perceptions, which were usually investigated through surveys or questionnaires. We do not provide percentages for each code in Tables 7–9 because, given that the total number of empirical studies is 102, the percentages are almost identical to the frequencies.

The results shown in Table 7 reveal that 84 studies of direct educational outcomes reported that FCs had a positive effect on basic language skills, content knowledge, and foreign language proficiency. Of these, 64 were concerned with the positive effect of FCs on foreign language proficiency, speaking skills, or listening skills. This result might be explained by the features of FCs. The main difference between FCs and traditional classrooms is that the teaching of content in FCs has been removed from the classes themselves and is often delivered to the students through video recordings, which can be viewed repeatedly outside of the class. In-class time can thus be used for discussion, presentations, or the extension of the knowledge provided in the videos. It is evident that students have more opportunities to practice listening and speaking in FCs, and foreign language proficiency is naturally expected. Only three studies reported that FCs had no effect or a negative effect on the development of foreign language proficiency, speaking, listening, and writing skills. Yan and Zhou (2021) found that after the FC model had been in place for one semester, college students’ reading abilities improved significantly, while there was no significant improvement in their listening and writing abilities. Yin (2016) reported that after FC had been implemented for one semester, there was no significant difference in college students’ speaking scores.

A total of 96 studies reported positive effects on indirect educational outcomes, including: boosting learners’ motivation, interest, or confidence; enhancing engagement, interaction, cooperation, creativity, independent learning ability, or critical thinking ability; fostering information literacy, learning strategies, learning efficiency, or self-efficacy; or relieving stress or anxiety. The most frequently documented indirect effect of FCs is improvement in students’ independent learning ability. Only one study found that the FC did not significantly increase student interest in the course (Wang, 2015). Similarly, only one study found that students’ anxiety in the FC was significantly higher than that in a traditional class (Gao and Li, 2016).

Learners’ satisfaction with FCs

Table 8 presents the results regarding learners’ satisfaction with FCs. Nine codes were used to categorize the different aspects of learners’ satisfaction investigated in the 102 empirical studies. Some researchers represented learner satisfaction using the percentage of students choosing each answer on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 5 (very satisfied), while others used average scores based on Likert scale values. For the purposes of our synthesis of findings, if the percentage is above 60% or the average score is above 3, the finding is categorized as satisfied; otherwise, it is categorized as not satisfied.

The results in Table 8 show that among the nine aspects investigated, teaching approach and learning outcomes were most frequently asked about in the research, and learners were generally satisfied with both. Only one study (Li and Cao, 2015) reported significant dissatisfaction; in this case, 76.19% of students were not satisfied with the videos used in college English teaching due to their poor quality.

Factors influencing the effect of FCs

Eleven factors were found to influence the effect of FCs; these are categorized in Table 9.

The results shown in Table 9 indicate that learners’ foreign language proficiency and self-regulation or self-discipline abilities are two important factors influencing the effect of FCs. Learners with high foreign language proficiency benefited more from FCs than those with low foreign language proficiency (Lv and Wang, 2016; Li and Cao, 2015; Wang and Zhang, 2014; Qu and Miu, 2016; Wang and Zhang, 2013; Cheng, 2016; Jia et al., 2016; Liu, 2016), and learners with good self-regulation and self-discipline abilities benefited more than those with limited abilities (Wang and Zhang, 2014; Lu, 2014; Lv and Wang, 2016; Dai and Chen 2016; Jia et al. 2016; Ling, 2018). It is interesting to note that two studies explored the relationship between gender and FCs (Wang and Zhang, 2014; Zhang and He, 2020), and both reported that girls benefited more from FCs because they were generally more self-disciplined than boys.

Studies with other research foci

There were six studies with other research foci, three of which investigated teachers’ attitudes toward FCs (Liao and Zou, 2019; Zhang and Xu, 2018; Zhang et al., 2015). The results of the surveys in these three studies showed that teachers generally held positive attitudes towards FCs and felt that the learning outcomes were better than those of traditional classes. However, some problems were also revealed in these studies. First, 56% of teachers expressed the desire to receive training before using FCs due to a lack of theoretical and practical expertise regarding this new model. Second, 87% of teachers thought that the FC increased their workload, as they were spending a significant amount of time learning to use new technology and preparing online videos or materials, yet no policy was implemented in the schools to encourage them to undertake this work. Third, 72% of teachers felt that the FC increased the academic burden students faced in their spare time (Zhang and Xu, 2018; Zhang et al., 2015). The final three studies include Cheng’s (2016) investigation of the mediative functions of college EFL teachers in the FC, Wang and Ma’s (2017) construction of a model for assessing the teaching quality of classes using the FC model, and Luo’s (2018) evaluation of the learning environment of an FC-model college English MOOC.