Ciudad de David, Panama – In hospitals around the world, the attire of medical staff conveys important messages to patients. A white coat often indicates professionalism. Surgical scrubs suggest cleanliness and sterility.

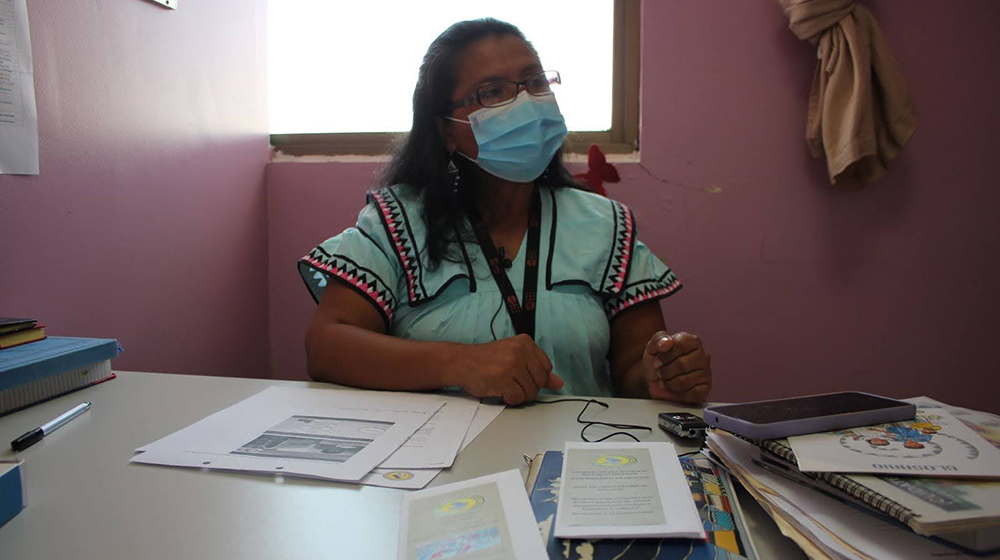

The bright blue and pink clothes worn by Eira Carrera, a cross-cultural interpreter at Jose Domingo de Obaldia Mother and Child Hospital in David, Panama, may not be common in hospital settings, but they are important. There is no change in the fact that it conveys a message.

“I am here dressed as Ngebe,” Carrera told UNFPA, the United Nations sexual and reproductive health agency. “That sets me apart from the hospital staff.”

Carrera is a member of Panama's indigenous Ngebe community. Her job at David's Maternal and Child Health Center is to liaise between Ngebe patients and the hospital's medical providers, who primarily speak Spanish.

This work is critical to closing the gap in health care access for Panama's Ngebe people, who, like other indigenous communities around the world, have long faced forced displacement, oppression and rights violations as a legacy of colonialism. be.

Today, the Ngebe people are the most marginalized in Panama, forced to contend with high rates of poverty, discrimination, and lack of access to health care.

As a result, pregnant Ngebe women often arrive at Karela's hospital with dangerous complications, and their lives are threatened by a health system unfamiliar to their language, culture, and values. The danger is only increasing.

“Pregnant women who visited the health center previously said they couldn't communicate, they didn't understand, and there was no consideration,” Carrera said. “But that has completely changed.”

Build a culture of consent

Between 2000 and 2020, Panama's maternal mortality rate decreased by nearly 25%. But this widespread progress obscures dangerous disparities affecting the country's ethnic minorities. For example, research shows that indigenous women in Panama are approximately six times more likely to die during childbirth than non-indigenous women.

“Women were dying at home giving birth,” said Gertrudis Saia, president of the Ngebe Women's Association. “We began meeting to identify the problem, look for solutions, and seek support from institutions and allies.”

Research reveals that Ngebe women struggle to meet their family planning needs and access quality maternal health services due to factors such as cost and distance . Abuse by health care providers also poses a problem.

“The Ngebe women said, 'The health center doesn't understand me,'” Carrera said. “Often they were told there was no space or were spoken to in a tone that made them feel scolded. And if women refused treatment, they were treated in a forced and compulsory manner. Sometimes I received it.”

To address these challenges, Ms. Sayre's association is working with David's Mother and Child Hospital to create a program aimed at lowering communication barriers between Indigenous patients and non-Indigenous health care providers. Launched a cross-cultural program to educate health care workers about cultural supports. delicate care.

Carrera says that since the hospital started a cross-cultural interpretation program, staff's approach to Ngebe women has improved dramatically, and patient consent for surgery plays a key role.

“If she doesn’t accept it, that’s respected,” Carrera said.

integration and inclusion

Today, José Domingo de Obaldia Hospital's evolving approach to inclusion extends from staff uniforms (many healthcare providers incorporate traditional Ngebe designs, patterns and colors) to walls in Spanish and Ngebere. It shows up in everything, down to the information posted on it. .

This is evident in the changing attitudes of providers. Karela pointed out that in the past, Ngebe women had been turned away by hospitals even though they had been walking for days.

In contrast, in 2020, one researcher quoted the hospital's obstetrics and gynecology director as saying: What you can do is show her empathy and make her feel welcome. ”

These small acts of solidarity and support add up to something bigger: an effort to tackle big social problems and save mothers' lives.