He needed care, not handcuffs. But in the district, police are the ones to go to when someone is in a mental health crisis. One way to look at it is through discrimination, the denial of services to people with disabilities.

The Justice Department agreed last week that there is a disconnect.

Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clark of the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division said in a statement Thursday that “relying on ineffective and potentially harmful responses deprives people with mental illnesses of equal access to important public services.” It can take away opportunities.”

The case is related to a lawsuit filed last summer by the ACLU on behalf of Bread for the City, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit that called the treatment a case of discrimination against people with disabilities. There is.

Yes, this shop, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, serves bread and other foods. Over time, the nonprofit organization grew to provide clothing, social services, legal services, and medical assistance. And the disconnect with care occurs when people come to us in a mental health crisis, whether it's a panic attack or suicidal thoughts.

“It's certainly traumatic for the people who need to be cared for,” said Tracy Knight, who has led social services programs at Bread for the City for more than 20 years. “This is traumatic for the provider who finds themselves in a situation where it's their only option. I'm sure it's traumatic for other customers and staff who witnessed this person being led away in handcuffs.” But it’s an unnecessary trauma for everyone involved.”

For more than 20 years, she has seen this scenario frequently. A staff member called 911 after someone came in asking for help saying he was feeling suicidal.

“And even if the person is completely non-violent, fully consenting, and willing to seek help voluntarily, that's the only way. [police] “The way we transport people is handcuffing them and putting them in the back seat of a car,” Knight said.

Thanks to years of messaging, the stigma of seeking treatment is waning. The slogan has meaning:

“Mental health is health.”

“Mental health is important.”

“Let's break the silence.”

We are more open than ever about our Zoloft prescriptions and treatment sessions. But crises test the limits of that progress. After all, the lawsuit says, police are the people most likely to respond if someone becomes seriously unwell.

It can be frightening and stigmatizing for those who have never been handcuffed, and re-traumatizing for those who have already been handcuffed.

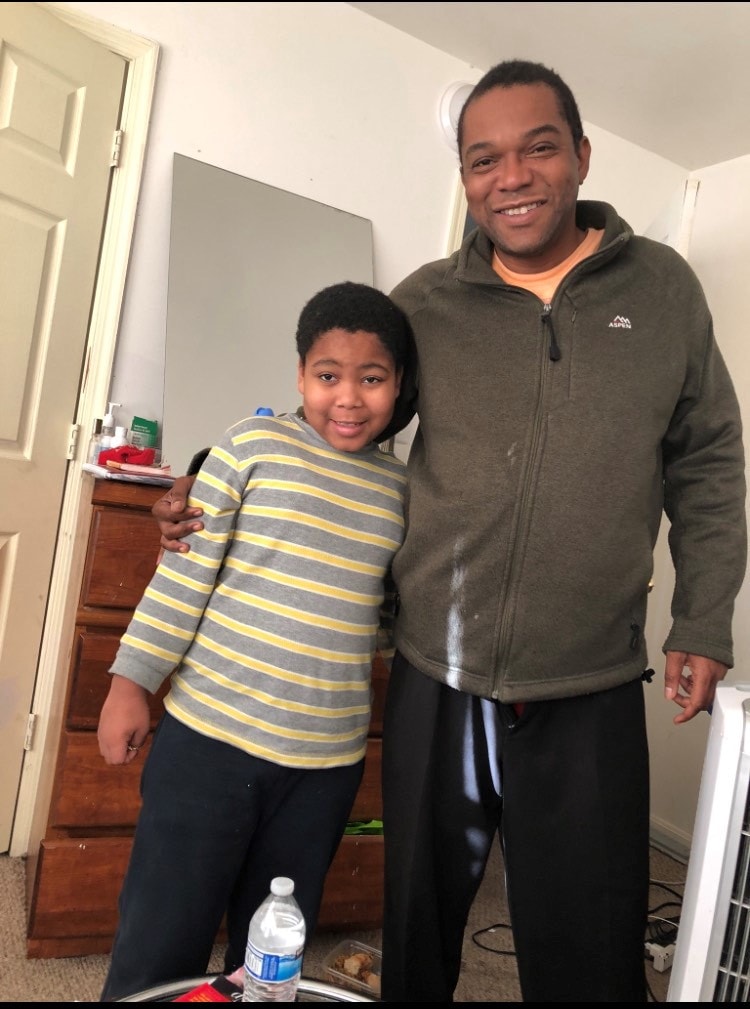

So did Olu's family. Her brother, who died two years ago from health complications at age 47, had a long history with police forces across the country.

His personality was gentle, she said. He was a storyteller who loved and spoiled his nephews dearly. When he was working on the West Coast as an executive pursuing his secret dream of becoming an actor, the police were called on him every time he felt unwell. It happened in California, New York, and Maryland.

“They can be scary because they show up with weapons. And who you get is a matter of luck,” said Olu, who is now an advocate for people with mental health differences. Ta. “I don’t know if I’m going to get Officer Friendly or Officer Ready to Shot.”

In some cases, police officers are trained to deal with mental health issues. It was part of the backlash against the ACLU lawsuit. This year, the Integrated Communications, Assessment, and Tactics (ICAT) training program will be taught to “all sworn members” of the D.C. Police Department.

“We want our officers to show empathy, passion, and compassion, but not be afraid to take the necessary law enforcement actions to protect our communities,” said Washington, D.C. Police Chief Pamela A. Smith. ” he said. DC Police Academy last year.

wonderful. wonderful. it's okay. Certainly better than in years past.

“But they are still police officers,” Olu said.

In Bread for the City, officers who help someone in crisis call the CRT, the police department's special community response team. This is the perfect solution for these situations. They are unarmed clinicians and counselors.

The only problem is that there are only about 44 of them. According to the ACLU's lawsuit, the organization only responds to 1 percent of necessary 911 calls.

It's a routine that Knight, a social worker colleague, is familiar with. They tried contacting his CRT team, but no one was available, so the next step was for him to call 911.

“So the police are going into a place where there are already people going through a mental health crisis,” Knight said. “There's probably already some level of anxiety and fear in this situation, and the presence of armed police just adds to that anxiety.”

This happens hundreds of times every year. But the rest of the people who aren't on the front lines only hear about it when things go bad – when shots are fired and someone dies.

According to a report by the National Alliance on Mental Illness, half of the people killed by police in our country had some kind of disorder.

“Police have become the default responder to mental health calls,” write the authors, historian David Perry and disability expert Laurence Carter-Long. They propose that in police responses, “mentally ill persons'' are presumed to be “a danger to themselves and others.''

It's time to move beyond slogans and rhetoric.

We hear it and we know it. Mental health care is just health care.

It is now up to our nation's leaders – those who can make the changes we seek – to do something.

correction

A previous version of this article misstated the name of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. This article has been corrected.