Some Nebraska lawmakers believe the state could use some help attracting special education teachers. State Sen. George Dungan said, “Nebraska, like the rest of the world, faces education shortages,” and the 2023-2024 Teacher Shortage Study found that special education has the highest deficit in Nebraska. It is an area where Among responding public schools, 24% of positions are unfilled (referring to positions filled by someone other than a qualified teacher or vacant), and approximately 9% of all special education positions remain vacant. was. Mr. Dungan sponsored his LB 964, which would provide student loan forgiveness for up to 25 students per year who enroll to become special education educators. The bill says it would only apply to students attending one of the state's universities or those affiliated with the University of Nebraska System. “The special education sector faces some of the most acute staffing shortages,” Dungan said. The bill was the subject of debate in the Legislature's Education Committee on Monday. Perhaps this profession is most needed by Nebraska families who need this education. Their loved ones,” Dungan testified Monday. Part of the bill would require recipients to find a special education job in Nebraska within one year of graduation and continue working in the Nebraska field for up to five years, or as long as the loan forgiveness was granted. It stipulates that “We believe that hiring more teachers requires creative and innovative policies, not only at the district level, but also at the state level,'' said Omaha City School Board members who spoke in favor of the bill. Chairman Spencer Head testified. The association also supports this bill. “We are in a crisis,” said Megan Pitratto, a middle school special education teacher who spoke on behalf of NSEA. “We just don't have enough graduates to fill the vacancies.'' No one testified against the bill.According to a fiscal analysis, implementing the bill would cost about $500,000 a year. About half of that money will go toward scholarships, and the other half will go toward paying for the work the two states need to administer and track the program.

Some Nebraska lawmakers believe the state could use some help attracting special education teachers.

“Nebraska, like the rest of the world, faces an education deficit,” said State Sen. George Dungan.

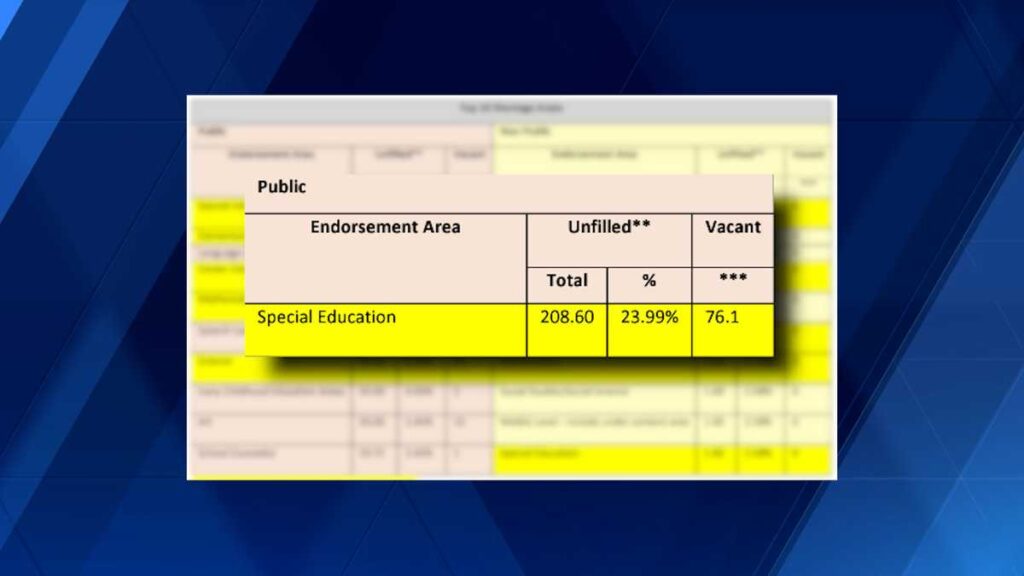

According to the 2023-2024 Teacher Shortage Study, special education is the area with the highest shortage in Nebraska. Among responding public schools, 24% of positions are unfilled (referring to positions filled by someone other than a qualified teacher or vacant), and approximately 9% of all special education positions remain vacant. was.

Dungan sponsored LB 964, which would provide student loan forgiveness for up to 25 students per year who enroll to become special education educators.

The bill says it would apply only to students attending one of the state's universities or those affiliated with the University of Nebraska System.

“The special education sector faces some of the most acute staffing shortages,” Dungan said.

The bill will be considered by the Assembly Education Committee on Monday.

“Perhaps this career is most needed by Nebraska families who need this education for their loved ones,” Dungan testified Monday.

Part of the bill would require recipients to find a special education job in Nebraska within one year of graduation and continue working in the Nebraska field for up to five years, or the length of time the loan forgiveness was granted. It is stipulated that this must be done.

Omaha Board of Education Chairman Spencer Head, who spoke in favor of the bill, said, “Recruiting more teachers requires creative and innovative policies not only at the district level but also at the state level.'' I think so,” he testified.

The Nebraska Education Association also supports the bill.

“We are in a crisis,” said Megan Pitratto, a middle school special education teacher who spoke on behalf of NSEA. “We just don’t have enough graduates to fill the vacancies.”

No one testified against the bill.

A financial analysis estimates implementation will cost about $500,000 annually. About half of that money will go toward scholarships, and the other half will go toward paying for the work the two states need to administer and track the program.