Bengaluru: On a chilly winter evening, last year, Sanjith G.S., a student of engineering in Bengaluru, realized he needed a hair dryer.

Bengaluru: On a chilly winter evening, last year, Sanjith G.S., a student of engineering in Bengaluru, realized he needed a hair dryer.

A quick online search led to many hair dryer options on the two familiar e-tailing platforms, Amazon and Flipkart. But to his surprise, Blinkit, known for delivering groceries, also popped up. What caught his attention most was the price tag—on Blinkit, a particular brand of hair dryer, selling for ₹999, was a tad cheaper when compared to the other online stores. While speed wasn’t a top priority, the swift delivery didn’t hurt.

Hi! You’re reading a premium article! Subscribe now to continue reading.

Subscribe now

Premium benefits

35+ Premium articles every day

Specially curated Newsletters every day

Access to 15+ Print edition articles every day

Subscriber only webinar by specialist journalists

E Paper, Archives, select The Wall Street Journal & The Economist articles

Access to Subscriber only specials : Infographics I Podcasts

Unlock 35+ well researched

premium articles every day

Access to global insights with

100+ exclusive articles from

international publications

Get complimentary access to

3+ investment based apps

TRENDLYNE

Get One Month GuruQ plan at Rs 1

FINOLOGY

Free finology subscription for 1 month.

SMALLCASE

20% off on all smallcases

5+ subscriber only newsletters

specially curated by the experts

Free access to e-paper and

WhatsApp updates

A quick online search led to many hair dryer options on the two familiar e-tailing platforms, Amazon and Flipkart. But to his surprise, Blinkit, known for delivering groceries, also popped up. What caught his attention most was the price tag—on Blinkit, a particular brand of hair dryer, selling for ₹999, was a tad cheaper when compared to the other online stores. While speed wasn’t a top priority, the swift delivery didn’t hurt.

“Within minutes, I had the hair dryer in hand, along with some savings,” said Sanjith.

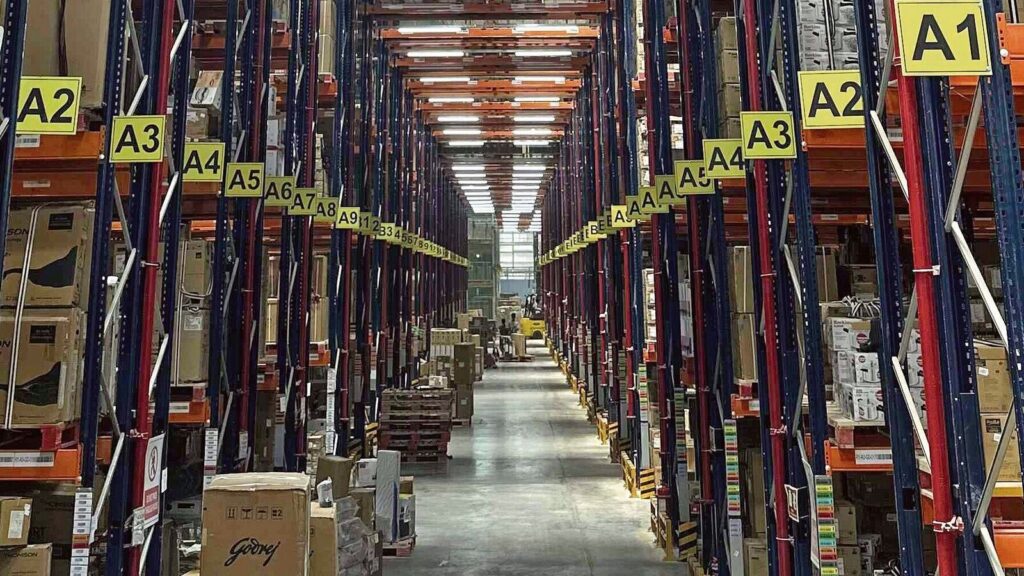

Blinkit, owned by Zomato, is a quick commerce company. So are Swiggy Instamart and Zepto. They mostly deliver goods to our homes super quick, within 15-20 minutes. These companies have set up dark stores or micro-fulfillment centres across many neighbourhoods in a city to facilitate the stocking, packing and fast dispatch of orders. Convenience-loving millennials in India’s large cities have lapped up their services—the gross merchandise value (GMV) of quick commerce, or the value of all goods sold, have jumped from a negligible $0.1 billion in 2020 to $2.8 billion in 2023, according to estimates by Redseer, an advisory firm.

All quick commerce companies started with groceries, or by selling stuff such as potatoes, tomatoes, mangoes, apples, rice and oil. But more recently, like Sanjith discovered, they stock everything from hair dryers and induction cooktops to smart watches and dildos.

This has become a headache for Flipkart, one of India’s largest e-tailing companies with revenue of ₹55,823 crore in 2022-23. Selling everything is its domain. That’s what the company, now owned by Walmart, pioneered in India for over 15 years. But this fortress is under threat.

Elara Capital, an investment banking firm, in a report published in April this year, stated that quick commerce is impacting the sales of traditional and e-commerce companies in cities where they are operational. “3-6% of the monthly FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods)/grocery spends may move to quick commerce platforms led by convenience,” it stated.

So, there’s an urgency within Flipkart to launch quick commerce to protect its turf. It could launch the service within weeks, some company employees told Mint. None of them wanted to be identified.

This would be the company’s third attempt. In 2015, Flipkart launched a quick service called Nearby to deliver goods within 60 minutes. It closed down as the unit economics did not make sense at that time. In 2020, the company tried the model again with a service called Flipkart Quick. It shut down for broadly the same reasons, the employees Mint spoke to said.

But the quick commerce model, which many industry observers wrote off even two years back, appears to be working now. “Based on what we’ve estimated, in 2024-25, quick commerce should be able to register explosive growth, 70-80% or in that range,” Kushal Bhatnagar, associate partner at Redseer, said.

According to the people Mint spoke to, Flipkart is currently gripped by the fear of missing out (FOMO). What can it do to capitalize on the quick commerce wave?

Flipkart didn’t respond to clarifications sought by Mint.

Early but not quick

Before delving into Flipkart’s strategy, let’s first understand what went wrong with its previous two endeavours.

Flipkart Nearby, launched in 2015, was a 60 minutes delivery service. Flipkart Quick in 2020 promised delivery in 90 minutes. Both the experiments were largely around delivery of food, vegetables and other grocery items.

The 2015 venture was a five-month pilot in Bengaluru. Flipkart was way ahead of its time—the term ‘quick commerce’ was not in vogue back then and the idea did not vibe with consumers, former employees said.

In 2020, expenses burdened Flipkart Quick. “The burn wasn’t making sense. There was less traffic on the website, which made it even more difficult when you are dealing with fruits and vegetables,” said a former employee of Flipkart Quick.

“Since there was less traffic, the company was buying less. When you’re buying less, you don’t get the cost-benefit,” said a current employee. The company was using its existing supply chain infrastructure for logistics, the person added. “The legacy supply chain was not designed for speed. It was designed for cost optimization—we optimized a lot on the shipment cost,” he said.

Flipkart Quick then struggled with inventory management.

Zepto has a weekly replenishment plan, which helps the company maintain higher in-stock numbers and better availability for customers. Flipkart, on the other hand, had a daily replenishment plan.

“On days when there was a sudden demand surge, many stock keeping units (SKUs) weren’t available,” a former executive said. “Let’s say you order an inventory of 15 breads and someone places an order for 15 breads because of some occasion. Breads, therefore, would be out of stock for other customers,” he said, adding that this impacted customer experience.

Zepto did not respond to Mint’s request for a clarification.

On 4 April, Albinder Dhindsa, the chief executive officer (CEO) of Blinkit, posted a short message on X, formerly Twitter. “PlayStation 5 on Blinkit. Launching tomorrow,” he wrote.

A ‘slim’ version of Sony’s latest gaming console is priced at ₹54,990. Blinkit promises to deliver it in under 20 minutes.

This made product managers at Flipkart rather nervous. “This is alarming for both Amazon and Flipkart,” one Flipkart employee said.

“The communication now is to re-prioritize the quick commerce project. We were working on improving customer experience in normal deliveries but that is not a priority now,” said a current employee.

The quick commerce project is being led by Hemant Badri, Flipkart’s senior vice president and group head of supply chain. A new business unit has been set up within Flipkart with a separate technology team. The message—it won’t be a half-hearted attempt this time. “We’ve built bigger and better teams. And there’s infrastructure being set up in parallel,” said another employee.

Like Blinkit, Zepto and Instamart, Flipkart is also setting up dark stores, which is at the heart of quicker deliveries. It plans to ready 1,000 such stores by the end of June, employees quoted above informed.

What could be Flipkart’s differentiator?

According to multiple current employees, the company is looking at a larger assortment of categories. “You will see electronics in the first release itself,” said a current employee. Electronics is also where Flipkart can differentiate because of the company’s existing relationships with manufacturers and sellers, as well as the opportunity to make fatter margins.

“Fruits and vegetables attract customers. But when someone buys electronics, it is profitable for the platforms. Flipkart’s wider range is going to be a differentiator,” said a current employee.

While the quick commerce infrastructure is being built, Flipkart is seeing a company-wide strategic change too—the entire organization is moving towards a more hyperlocal approach. “We are also looking at being a lot more relevant on the normal groceries front. Some routes in Bengaluru, for example, are being readied for same-day deliveries and next-day deliveries,” said a current executive.

Improving economics

Meanwhile, the despair around unit economics is slowly giving way to hope. One big lever is advertising. “Quick commerce appeals very aggressively to the FMCG sector, which is 40% of India’s advertising expenditure,” Karan Taurani, senior vice president at Elara Securities, said.

“With quick commerce, brands can see the response of a new product that they have launched in a day,” Bhatnagar of Redseer chimed.

Second, dark store efficiencies have gone up, he added. If a micro market has a significant Gujarati population, for example, quick commerce companies now stock goods favoured by the community. If a dark store is able to serve a significant demand in a catchment area, the fixed costs—such as rents or delivery partner payouts—get offset, leading to better platform economics, Bhatnagar explained.

It isn’t easy

Founded in 2007 by Binny Bansal and Sachin Bansal, Flipkart started as an online bookstore. It has traditionally not been a fast delivery company, with most deliveries taking over two days. This hasn’t changed over the years. It has focused on bigger warehouses instead of fragmented ones. Amazon has more fragmented warehouses, which helps it deliver within 24 hours.

The legacy business of both Swiggy and Zomato, on the other hand, pivoted around faster food deliveries. That experience has helped the two companies in the quick commerce business. The massive overhaul of logistics that Flipkart requires to be in the quick commerce game is therefore daunting.

“Flipkart is a more national company. They have divided the India market into different cities, into different segments and they ensure the right selection and supply,” said an industry expert who didn’t want to be identified. “However, the quick commerce business requires local execution. Flipkart will have to work hard to develop and adapt to a more fast, agile model. The existing companies understand the hyperlocal play better,” the executive added.

“Companies like BigBasket started much earlier when compared to Instamart, Zepto or even Blinkit. But still, they haven’t been able to evolve themselves in terms of quick commerce,” Taurani said.

A second challenge for Flipkart would be market share. By now, companies such as Blinkit and Zepto have already created muscle memory for customers residing in cities, market watchers said. When you want a quick delivery, you know these platforms are the options.

That leaves Flipkart with the non-metros, where it is a dominant platform. But quick commerce is yet to pick up pace in tier 2 or tier 3 markets.

“Amazon’s transition would likely be more seamless due to existing customer trust in purchasing non-essential items on the platform. Flipkart, with its limited penetration in metros, will require more time,” Satish Meena, an independent e-commerce analyst and advisor at Datum Intelligence, said.

We will have to wait and watch if electronics can indeed be a differentiator. In the absence of a differentiator, Flipkart would need to discount, harming the unit economics. While two current employees said the only differentiator could be a wider assortment, there’s a problem here too. The categories that Amazon and Flipkart deal with—like electronics and fashion—are discovery driven, said Meena.

“Apart from the impulse purchases, your grocery brands are almost defined. You don’t change your atta or your bread brand. You just repeat almost everything. Quick commerce companies know what SKUs are being ordered and then stock accordingly,” he said.

Growth project

Nonetheless, the quick commerce bet is critical for Flipkart. Of course, it has to defend its turf. But it also has to grow its GMV, which, in turn, will determine the company’s valuation. A current employee succinctly pointed it out, calling the venture a “growth project”.

On 18 March, PTI, a news agency, reported that the e-tailer’s valuation had taken a hit. Citing transactions by its US-based parent, Walmart, it said that as of 31 January 2024, Flipkart was valued at $35 billion, down from $40 billion in 2022-23. The decline in value was attributed to the separation of the company’s fintech arm, PhonePe, into an independent entity.

Kalyan Krishnamurthy, the Flipkart group’s CEO, has communicated to employees on several occasions about his desire to take the company public “after reaching a certain valuation”. We don’t know what that number is but there is definitely a lot at stake for the e-tailer’s quick commerce venture.