CONCORD, Calif. — A year before Aytin Quinn's son was old enough to start kindergarten, she and her husband had the option of enrolling him in “transitional kindergarten,” a program offered free of charge by California elementary schools for about four years. I had. Old man.

Instead, they sent their son Ethan to a private day care center in Concord, California, at a cost of $400 a week.

Although the academic focus of transitional kindergarten was appealing, Ethan ended up in a half-day program, which limited his after-school care options. It was also convenient for my parents, who work in the hospitality industry, to be able to send Ethan and her younger brother to the same day care, and to be able to drop them off in the morning and pick them up in the evening from one place. .

“Ethan is going through changes at home with the birth of his new brother and will likely be starting a new school as the youngest child,” Quinn said. “This also does not include transport concerns, such as class pick-up and drop-off or after-school child care elsewhere. There are many things to consider.”

The investments California and other states have made in public preschools have helped many parents navigate a child care crisis where quality options for early learners are lacking and often unaffordable. . However, many parents claim the program is ineffective for their families. Even when Pre-K runs throughout the school day, working parents struggle to find child care before 9 a.m. and after 3 p.m.

No state has more ambitious plans for universal preschool than California. The state plans to expand transitional kindergarten eligibility to all 4-year-olds by fall 2025 as part of a four-year, $2.7 billion expansion. The idea is to offer a two-year kindergarten program to quickly prepare children for the rigors of elementary school education.

Enrollment in option programs is increasing more slowly than expected. Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom estimated that about 120,000 students would enroll last year. However, average daily attendance was approximately 91,000 people.

Average daily attendance through December this year was about 125,000, said Sara Cortez, a policy analyst with the California Office of Legislative Analysis.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some families no longer see the same value in traditional preschool. Others may be equally satisfied with a program without an academic component. School days that require noon pick-up can shift families to private day care, Head Start programs, and other alternatives that provide full-day care.

Some schools that accept transitional kindergarten offer childcare before and after instruction, but not all.

“If a school does not offer such comprehensive child care at the beginning or end of the school day, the only option parents have may be to remain in the child care center,” said Deborah Stipek, former dean of the School of Education. he says. Stanford University advocates for equitable access to early childhood education in California.

States such as Iowa, Michigan, New Jersey, and Washington offer early learning options similar to transitional kindergarten, and the benefits of this program are proven.

In California, the program is taught by educators with the same certification requirements as kindergarten teachers, but a five-year study found that students entered kindergarten with better math and reading skills. Ta. In Michigan, the kindergarten transition program is not implemented statewide, but the program has led to increases in her third-grade math and English test scores. However, a California study found that scores on such tests did not increase in third and fourth grade.

“Kids have an opportunity to become familiar with the school environment before they enter kindergarten,” said Anna Shapiro, a policy researcher at RAND University who has studied the effectiveness of early childhood programs for about a decade and analyzed Michigan's TK program. talk.

Another benefit of transitional kindergarten is that it is free.

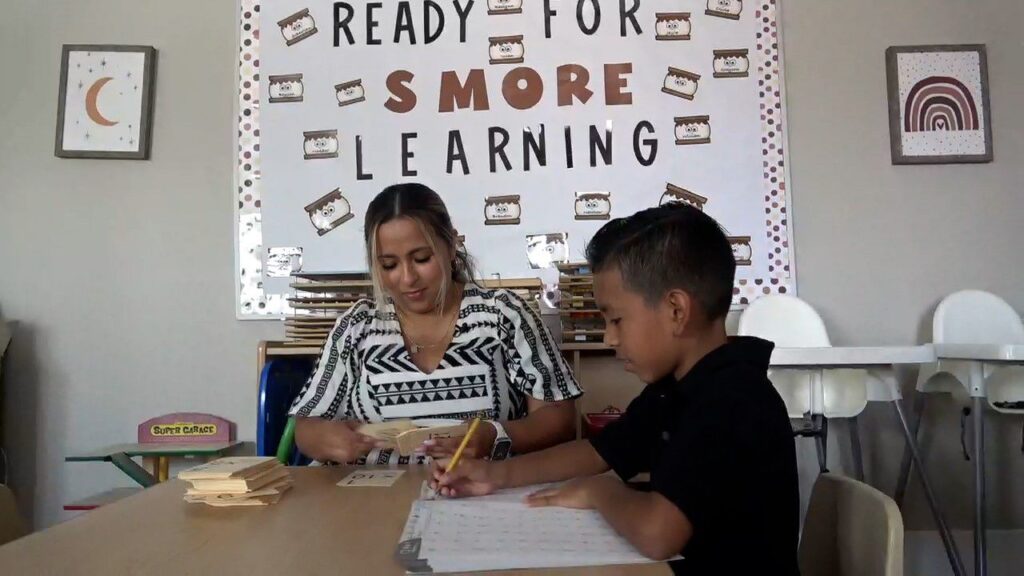

Maria Maldonado, a mother of seven who works at a deli in Los Angeles, enrolls her 4-year-old daughter Audrey in transitional kindergarten at Para Los Niños Charter Elementary School. Her daughter seems to like it so much, Maldonado said, that she's willing to pay for it even if it's not free.

The program also includes after-school care, so Audrey remains at school from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. Audrey is learning to read and write, she can count to 35, and her mother wants her to stay at school longer if her parents arrive well before her pick-up time. Said.

Maldonado only wishes other children had heard about the program sooner. She said she felt drawn to the school after visiting and speaking with her teachers.

“Academically, you have to learn everything you're taught. But if the atmosphere is good, it's a combination that makes kids happy. As a result, this girl loves going to school. ” she said.

As of this school year, California's transitional kindergartens were only admitting 4-year-olds who would turn 5 by early April. This fall, slots will be expanded to include more children in a phased expansion.

For Ethan's parents, the full-day care at his Kindercare-run day care center, along with its emphasis on play-based learning, were key factors in their decision to send Ethan there. .

“Some families choose to stay with us because we provide full-time, year-round care,” said Margot Gould, senior manager of government relations for KinderCare, which operates in 40 states.

Ethan's father, Scott Quinn, remembers thinking, “How bad could this be?” When you opt out of transitional kindergarten. But he was disappointed to see Ethan, one of the oldest children in his day care class, pick up on the behavior of children several years younger than him.

“In hindsight, it would have been better to send him to school and spend time with other kids his age and older,” he says.

Aitin Quinn also said she feels remorse after seeing Ethan no longer meet his old needs, such as naps. The couple considered enrolling him in TK in the middle of the school year, but ultimately decided it would cause too much stress managing his work schedule.

Raising Ethan was her first exposure to the fragmented landscape of early education, and she said she wished she had started considering her options before she became pregnant.

“Easier said than done,” she said. The Quinns plan to move to Connecticut this year to be closer to family and are considering preschool options for Ethan. “We will definitely get him into public kindergarten. Not only is he ready, but so are we.”