LOS ANGELES (AP) — Globe-trotting Associated Press correspondent Terry Anderson was snatched off the streets of war-torn Lebanon in 1985 and held for nearly seven years, making him one of the longest-held hostages in the United States. died at the age of 76. .

Mr. Anderson, whose best-selling 1993 memoir “The Lion's Den'' chronicled his abduction, torture and imprisonment by Islamic extremists, died Sunday at his home in Greenwood Lake, New York, his daughter Slome Anderson announced.

Anderson died of complications from recent heart surgery, his daughter said.

“Terry showed great courage and determination, both in his journalism and during his years as a hostage, deeply committed to witness reporting on the scene. I am so grateful for the sacrifices I have made as a result of my work,” said Julie Pace, executive vice president and editor-in-chief of The Associated Press.

“He never liked being called a hero, but everyone kept calling him that,” Slome Andersson said. “When I met him a week ago, my partner asked him if there was anything on his bucket list or something he wanted to do. He said, “I've lived so much, I've done a lot of things.'' I'm happy. ”

After returning to the United States in 1991, Anderson lived an itinerant life, giving public speeches, teaching journalism at several prominent universities, and occasionally operating blues bars, Cajun restaurants, horse ranches, and gourmet restaurants. I also managed the.

He also suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and won millions of dollars in frozen Iranian assets after a federal court concluded that Iran was involved in his arrest, but then Most of it was lost to bad investments. He filed for bankruptcy in 2009.

After retiring from the University of Florida in 2015, Anderson settled on a small horse ranch in a quiet rural area of Northern Virginia that he discovered while camping with friends. `

“I live in the country, and it's a nice place with decent weather and quiet, so it's okay,” he said with a laugh in a 2018 interview with The Associated Press.

In 1985, he was one of several Westerners abducted by members of the Shiite Islamic organization Hezbollah during the war that plunged Lebanon into chaos.

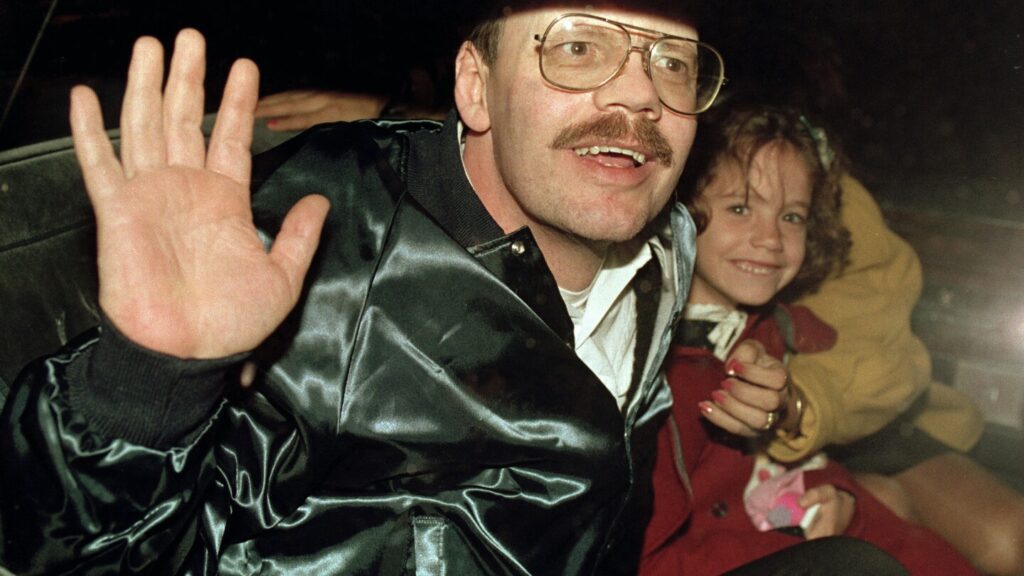

After his release, he returned to a hero's welcome at the Associated Press' New York headquarters.

As The Associated Press' chief Middle East correspondent, Anderson reports on the escalating violence gripping Lebanon as the country is at war with Israel and Iran funds extremist groups seeking to overthrow the government. I've been reporting on it for years.

On March 16, 1985, he was on a day off to play tennis with former Associated Press cameraman Don Mel, and as he was dropping Mel off at his home, gun-wielding kidnappers grabbed him from his car. I dragged it out.

He said he was likely targeted because he is one of the few Westerners still in Lebanon and his role as a journalist aroused suspicion among Hezbollah members.

“Because, in their words, people who go around asking questions in difficult, dangerous places must be spies,” he told Virginia newspaper The Review of Orange County in 2018. Ta.

What followed was nearly seven years of brutality, during which he was beaten, chained to walls, threatened with death, often had a gun to his head, and was often kept in solitary confinement for long periods of time.

Mr Anderson was the longest held of several Western hostages taken by Hezbollah over the years, including Terry Waite, a former envoy to the Archbishop of Canterbury, who arrived to negotiate his release. Ta.

According to his and other hostages' accounts, he was also their most hostile prisoner, constantly demanding better food and treatment, discussing religion and politics with his captors, and using sign language with other hostages. It is said that he told them where the messages were hidden so that they could have personal communication with them.

He was able to maintain his quick wit and dry sense of humor throughout the long ordeal. On his last day in Beirut, he called the leader of the kidnappers to his room and told him that he had heard false radio reports that he had been released and was in Syria.

“I said, 'Muffmound, listen, I'm not here.' I'm gone, baby. I'm on my way to Damascus.' And we both laughed.” he told Giovanna Dell'Orto, author of “The Associated Press' Foreign Correspondents in Action: From World War II to the Present.”

He later learned that his release was delayed because the third party to whom the kidnappers had planned to hand him over left for a tryst with his mistress and had to look for someone else.

Anderson's humor often masked the PTSD he admitted to suffering from in subsequent years.

“The Associated Press asked several British clinical psychiatrists who are experts in hostage decompression to counsel my wife and me, and they were very helpful,” he said in 2018. “But one of the problems I had was that I wasn't fully aware of the damage that was being done.”

“So, you know, when people ask me, 'Are you done yet?' Well, I don't know. No, it's not. It's out there. I don't think about it too much these days. Well, it's not the center of my life, but it's there.

At the time of his abduction, Anderson was engaged to his wife, and her future wife, daughter Surome, was six months pregnant.

The couple married soon after their release, but divorced a few years later, and although they remained on friendly terms, Anderson and her daughter were estranged for years.

“I love my father very much. He has always loved me. I didn't know it because he couldn't show it to me,” Slome Anderson said in 2017. He told the Associated Press in 2017.

Father and daughter reconciled after the publication of her critically acclaimed book, Hostage Daughter, in 2017. In it, she said, she traveled to Lebanon to confront one of her father's kidnappers and ultimately forgive her.

“I think she did an extraordinary thing and went through a very difficult personal journey, but I also think she accomplished a pretty important piece of journalism through it,” Anderson said. “She's a better journalist than I am now.”

Terry Alan Anderson was born on October 27, 1947. He spent his childhood in the small Lake Erie town of Vermilion, Ohio, where his father was a police officer.

After high school, he turned down a scholarship to the University of Michigan and joined the Marines, rising to the rank of sergeant while serving in combat during the Vietnam War.

Upon returning home, he enrolled at Iowa State University, graduated with a double major in journalism and political science, and immediately took a job at the Associated Press. He reported from Kentucky, Japan and South Africa before arriving in Lebanon in 1982, just as the country was in turmoil.

“In fact, it was the most fascinating job of my life,” he told The Review. “It was intense. There's a war going on – it was very dangerous in Beirut. It was a terrible civil war and it lasted about three years until I was kidnapped.”

Anderson was married and divorced three times. In addition to his daughter, he is survived by another daughter from his first marriage, Gabrielle Anderson; sister Judy Anderson; and his brother Jack Anderson.

“My father's life was marked by extreme suffering while he was held hostage, but in recent years he has found a quiet and comfortable peace.'' , the Homeless Veterans Protection Committee, and many other incredible humanitarian efforts,” Slome Anderson said in a statement Sunday.

Slome Anderson said memorial arrangements are pending.

—-

Biographical material for this obituary was prepared by former Associated Press reporter John Rogers. Associated Press journalist Andrew Meldrum contributed from New York.