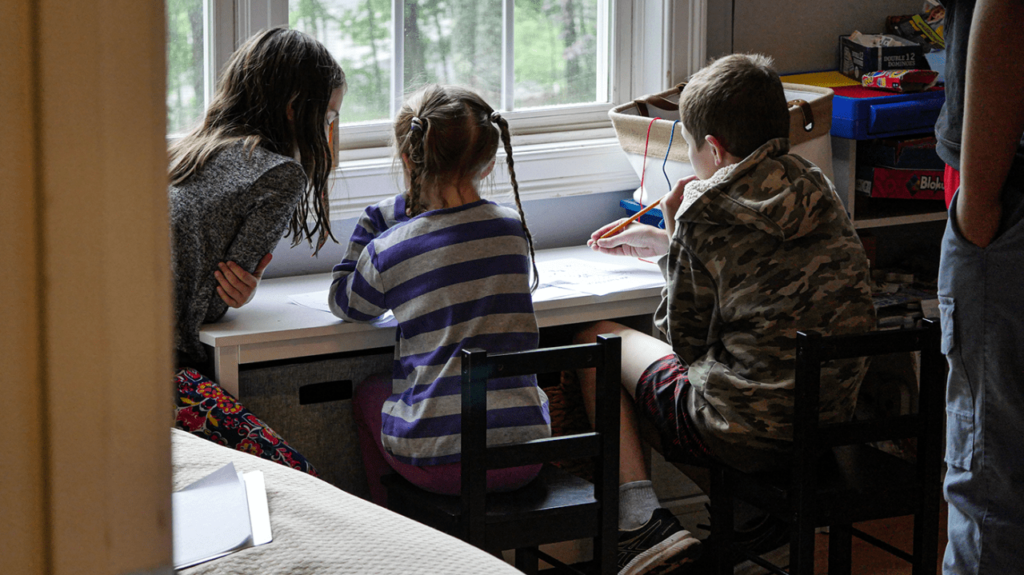

- Since the beginning of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, the United States has seen a surge in the creation of new microschools.

- The National Microschooling Network estimates that there are approximately 95,000 microschools in the country. The median microschool enrolls 16 students.

- Because no regulatory agency is solely responsible for tracking microschools, it is difficult to determine how popular they are becoming.

Microschools have skyrocketed in popularity since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

With a median student population of 16, the small school is said to be a modern reinvention of the one-room schoolhouse, where children of different ages receive individual instruction from teachers in the same room.

Supporters see them as liberating. However, skeptics are concerned about the quality of their education.

According to Dan Soifer, CEO of the National Microschooling Center, how many microschools existed in the United States before 2020, with most taking the form of informal learning pods? It's unclear whether or how many more schools opened in the early days of the pandemic.

But that number “definitely jumped” during the 2020-21 school year, Soifer told The Hill.

Soifer said about 1.5 million children currently attend one of the country's 95,000 microschools, about the same number as attend Catholic schools.

Proponents of microschools argue that they offer some students, especially gifted and learning disabled students, greater opportunities for academic and social growth than traditional schools. claim that there is.

At Sphinx Academy, a microschool based in Lexington, Kentucky, nearly all of its 24 students are “twice outstanding,” according to the school's president. That means someone is gifted in one academic field, but has one or more learning disabilities, such as ADHD or dyslexia.Jennifer Lincoln.

“We have gifted education and special education, but there aren't many resources for students where those two overlap,” Lincoln said.

She said Sphinx's small classroom sizes and individualized instruction allow students with varying levels of proficiency in different subjects to receive the attention they need.

Microschools can offer some children with physical or mental health problems an easier way to study than traditional schools.

For example, 16-year-old Leila Robertson was homeschooled during elementary school and homeschooled during the pandemic because of poor health before enrolling at Sphinx.

“I got to the point where I wanted to go back to school, but I thought a big school would be overwhelming,” Robertson told The Hill. “It wasn't a calm environment to work in.”

Robertson ultimately decided to attend the Sphinx because of its small size.

Microschools are also appealing to children who don't feel like they fit in at other schools.

This was the case for Madeline Michen, a 15-year-old who struggled to integrate into her private religious school in Lexington during the pandemic.

After observing a student for a day, she quickly realized that Sphinx Academy was the place she wanted to attend.

“I'm gay, and I saw a lot of other gay students and thought, 'Wow, they're so open and accepting here,'” Mischen said.

Sphinx Academy is a nationally accredited and Kentucky accredited school. However, the microschool world is an exception in this regard.

There is no single regulatory body overseeing microschools, which experts worry means there is no quality backstop to ensure children receive the education they deserve.

Most microschools are also not accredited. In a survey of 400 microschools nationwide shared with The Hill by the National Microschooling Center, only 16% said they were accredited in their state.

This is because many microschools operate as learning centers for home-schooled students and therefore do not require accreditation.

Other schools function as private schools and do not need to be accredited in most states or have certified teachers.

The world of private K-12 school accreditation in the United States is notoriously opaque. Education Next reports that there are no federal accreditation requirements for K-12 schools that “require schools to meet performance standards.”

At the state level, laws certifying private schools vary. Accreditation is rarely legally required for private schools, and is only required for public schools in about 20 states, the paper said.

For example, Florida, currently a hotbed of microschools, does not require accreditation of K-12 schools and accreditation, or lack thereof, is not commonly reported.

Nevada, another state with a growing microschool population, also does not require microschools. And neither state, like other states, requires private school teachers to have a teaching license.

Jen Jennings, director of Princeton University, said a lack of oversight and clarity about what classes are offered in microschools could lead to the U.S. eventually getting rid of one-room school buildings and moving toward more organized, integrated schools. The university's education and research department said it partially reflected the concerns that led it to adopt a new school system.

As a result of that change, states promised children a certain level of quality of education, Jennings added.

“So the concern about microschools and state-funded education without a quality backstop is that you never know what your kids are going to get,” Jennings said.

Concerns about microschools not being accredited occur most frequently in states that have education savings accounts or voucher programs, Soifer said.

In these programs, states set aside funding for students who opt out of the public school system and choose private or charter schools.

Last year saw a surge in states introducing or expanding school voucher programs, including Florida, Iowa, Utah and Oklahoma.

“The concern with a system like this is that the people who are receiving the money on behalf of the students are doing the right thing,” Jennings said.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.