FARGO — Education is of paramount importance to developing communities, and as soon as people settled in Fargo and Moorhead, they sought to establish education for their young people. Naturally, the first teachers were women.

Here is what is known about some of these important women and the educational legacies they created and that area schools continue to carry on today.

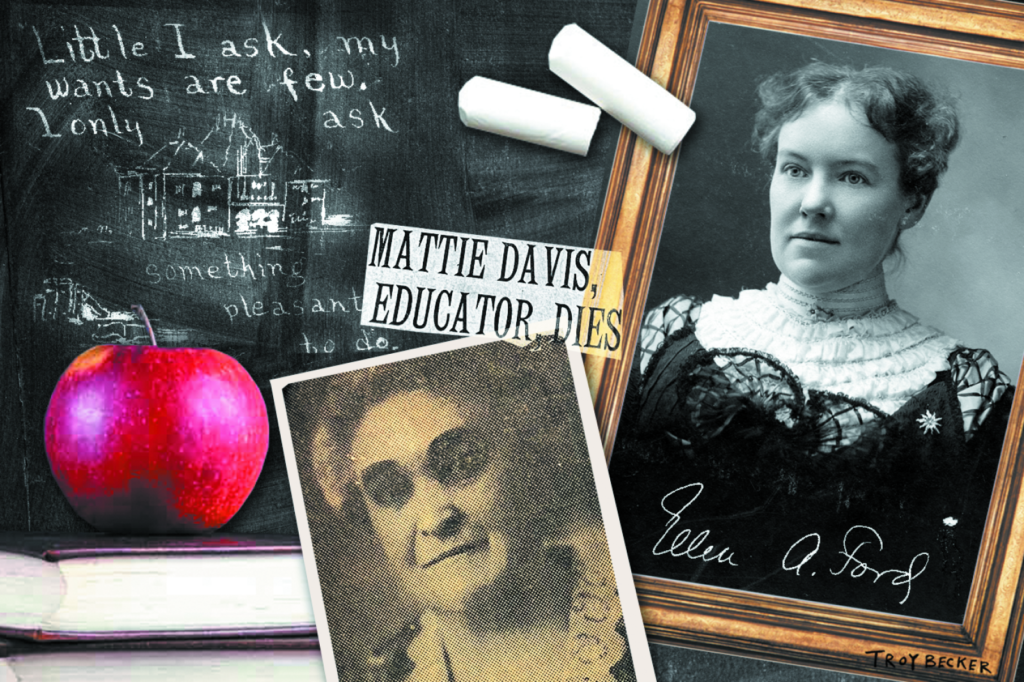

In 1872, Fargo was barely a tent pitched along the newly constructed railroad across the Red River from Moorhead. In a small log cabin, a teenage girl named Marcy Nelson receives the auspicious nomination of Fargo's first schoolteacher. The private school Nelson taught at had been established two years before the public school. It is a mystery whether she continued her teaching in public schools, but she married a local man named Eben Knight. However, Marcy died of typhoid fever in 1878, cutting her life short.

Ten years later, Lord Livingston was busy establishing a college to educate teachers on the Moorhead side of the Red River. When his 29 students arrived on campus in August 1888, Lord and his four teachers greeted them. Louise McClintock, Music and History. Elizabeth Clark, English Language and Literature. and Ellen Ford in algebra and Latin. According to Joseph Kise's History of Moorhead State University, teachers were paid a salary of $800.

Contribution / MSUM Archive

Not much is known about Clark. According to her school records, she taught English, grammar, literature, and art in her first grade and dropped out at the end of that grade. According to an article in the St. Paul Globe dated May 28, 1884, she may have been Elizabeth Clark, who graduated from Mankato Normal School in 1884 along with 11 other graduates. It is also not known what Mr. Clark did after his first year teaching at Moorhead Normal School.

Meanwhile, McClintock taught vocal music, history, and geography for two years and returned in 1895. By that time, she had married Thomas C. Kurtz, an engineer for the Northern Pacific Railroad and the first president of Moorhead Normal. Resident director. Although Louise was at the school for a short time, she made a strong impression on her students, especially after her return. One student said: Kurtz is the best music teacher at this school. ”

Shortly after Thomas Kurtz was appointed to a second term, he left school and moved his family to Montana, where he worked in a bank. Louise and Thomas had his two sons. John was born in 1897 and Harry was born in 1899. Louis died in Minneapolis in 1929 when he was 73 years old.

“It doesn't fit.'' Teacher

Ellen Ford never married or had children, but she had a successful career in education. She graduated from Syracuse University in 1894 at the age of 29, and after earning her bachelor's and master's degrees in Latin, Ellen taught in New York, and then she worked as a high school principal in St. Peter, Minnesota. I did.

After a year in the position, Lord hired her to teach at Moorhead Normal School. According to Clarence Glassrud's Normal History of Moorhead, she actually took a pay cut from her position as principal, but she was willing to take a pay cut in order to teach under Lord's guidance. That's what it means. Ellen's qualifications as a teacher were “unmatched,” according to Clarence Glasrud's speech in 1975, when the school became Moorhead State University, and that she and the other original teachers at the school It is said that he has set an “impossibly high standard'' for his guidance.

Contribution / MSUM Archive

Ellen was such a great teacher that when Lord left Moorhead Normal in 1899 to run the newly formed Eastern Illinois Normal School and University, she was one of the three people he took with him. was one of the teachers. According to “Eastern Illinois State University: 50 Years of Public Service,'' the Illinois Governor and Board of Education were reluctant to this idea and instead insisted that the teaching position be given to an Illinois resident.

Lord scolded this idea, saying, “Why shouldn't every state have the best teachers in the country, no matter where they live?” Eventually, all three teachers in Minnesota followed the Lord, and within a few years, two more joined the faculty.

Ellen's announcement of her resignation in November 1899 surprised the Moorhead campus, as described in an article in the Moorhead Independent.

“This is unexpected, and only the students themselves know how much being removed from the classroom will feel,” the anonymous author wrote. “They learned to love and respect Miss Ford not only as a great teacher, but also as an ideal woman.”

The author wrote that with Ellen's departure, “a large part of the school will be lost,” but that everyone in the community wishes her well for the future. President Frank Weld hosted a farewell reception for Ellen on his December 21, 1899, thanking Ellen for his 10 years of service to the school.

Eren's future was certainly bright.

According to a history of the eastern Illinois school, Lord relied heavily on Ellen and another Moorhead teacher (the third was on vacation) in developing the new school's curriculum. Officially joining the faculty in January 1900, Ellen quickly became an integral member of the faculty, earning the title of first dean of the faculty college, a position he held from 1918 until his retirement in 1934. I did.

Ellen also played a key role in supporting the transition from normal school to four-year university, writing in 1929 that “six years of most arduous work were required to separate the new from the old. The work was not fully completed until 1926,” he recalls.

On May 6, 1933, Lord contracted bronchitis and never recovered. He passed away on May 15th. His wife had passed away nine years earlier, and Ellen coordinated her funeral arrangements, enlisting key staff and community members to serve as pallbearers and honorary attendants for her mentor and friend. Even though Ellen was eligible to retire, he remained in office for an additional year to assist in the transition to the new president.

She retired in 1934 after more than 30 years at Eastern Illinois. Ellen was described by one of her colleagues as “She knows everything about this school and would definitely be the person to lead any department.''

Ellen returned to her hometown of Syracuse, New York, and spent the rest of her life close to her family. But she never forgot her ten years at Moorhead, as evidenced by her 1935 letter she wrote regarding materials she donated to her school. She wrote that her “ten years of her joyful life were spent in Moorhead,” and she fondly remembered her “fun group” of friends. “I love my school and town and am glad to know they are thriving,” Ellen wrote.

Ellen died in 1948 at the age of 83.

In 1959, a new residence hall at what is now Eastern Illinois University was named Ford Hall in Ellen's honor.

Cass County's first female superintendent

Mattie Davis never had children of her own, but just like Ellen, she influenced thousands of young people through her chosen profession.

Born in Canada in 1856 while his parents were visiting, Mattie spent the first few years of his life in New York before the family moved to Plainview, Minnesota, where his father worked as a sheriff. The eldest of 10 children, Mattie grew up helping to care for his younger brothers and sisters, and likely found teaching to be a natural fit for him.

She taught for several years before marrying Dr. EC Davis at the age of 28, but sadly the couple were struck by typhoid fever shortly after their marriage. Matty recovered, but her husband did not. A June 18, 1933 forum article notes that Mattie resumed her education to “partly forget” her grief, leaving the town full of her memories and moving with her younger brother Lewis to the Dakota Territory. reported that he jumped at the chance to move to the United States.

“Trading the green hills of Minnesota for a vast sea of undulating grain fields and endless wildflowers,” Mattie first taught eighth grade in Casselton and eventually became superintendent there. After that, I moved to a classroom in Fargo. Angela Boleyn wrote in a 1933 article, “She was ambitious for her own spiritual progress and had endless things to offer her students outside of her regular classes.”

In 1896, Mattie was elected Superintendent of Cass County, becoming the first woman to hold that position. She said in her speech in 1926 that she had to shovel through the snow to get to the courthouse in order to take up her new office. One of her first actions was to create a training program for her teachers in 1897. She also created a corn growing contest, which eventually spurred the establishment of her 4-H club in the state.

But that's not all Matty did. She was an early organizer of the group that led to the creation of the Parent-Teacher Association, which helped establish unifying goals for all students in all grades.

Mattie also fought for laws requiring students to be taught about drug and alcohol prohibition, and campaigned for a mill levy to establish a public library, passed in 1900. Sources say Fargo's first library opened in the basement of an old Masonic temple. Neighbor's column about Matty.

Education wasn't the only thing she focused on. A leader in the suffrage movement, she chaired the resolutions committee of the State Federation of Women's Clubs. She advocated for the city of Fargo to continue hiring female police officers and led a fundraising effort to install a sculpture of Sakawea on the grounds of the state capitol. She spoke at the sculpture's dedication in 1910, the same year she resigned as Cass County superintendent and became vice president of the Northern School Supply Company in Fargo.

Among North Dakota's pioneering female teachers, Mattie is described as “resourceful, fearless, proactive and persistent in her efforts to improve the schools in her home state.” It has been praised as She did all that and more.

Mattie died in 1936 at the age of 80. She is buried next to her husband in Plainview, Minnesota.