In Anchorage, wealthy families go on ski trips and other long vacations with the expectation that their children can keep up with schoolwork online.

In Michigan's working-class areas, school administrators have tried almost everything to boost student attendance, including pajama days.

And across the country, students with heightened anxiety are choosing to stay home instead of going to class.

In the four years since the pandemic shuttered schools, U.S. education has struggled to recover on many fronts, from learning loss to enrollment to student behavior.

But perhaps no problem is as persistent and pervasive as the surge in student absenteeism. This problem goes beyond demographics and persists long after schools reopen.

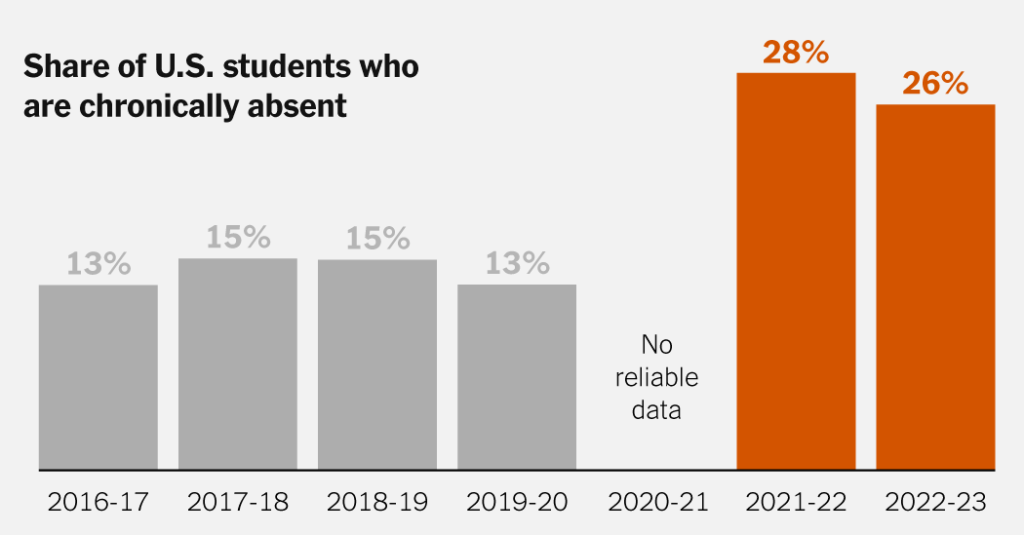

Nationally, an estimated 26% of public school students were considered chronically absent last school year, up from 15% before the pandemic, according to the latest data from 40 states and Washington, D.C., compiled by the conservative American Enterprise Institute. did. . Chronic absenteeism is typically defined as missing at least 10 percent of the school year, or approximately 18 days, for any reason.

Increase in chronic absenteeism, 2019-23

By local child poverty rate

By length of school closure period

By racial composition of the district

Source: Results analysis of data from Nat Malkus of American Enterprise Institute. Districts are grouped into highest, middle, and lowest thirds.

This increase is occurring in neighborhoods large and small, and across incomes and races. Chronic absenteeism rates in school districts in wealthy areas nearly doubled from 10% before the pandemic to 19% in the 2022-23 school year, according to a New York Times analysis of data.

Poor communities are facing an even bigger crisis, starting with rising rates of student absenteeism. About 32% of students in the poorest districts were chronically absent in the 2022-23 school year, up from 19% before the pandemic.

Even districts that reopened quickly in fall 2020 during the pandemic saw significant increases.

“The problem has gotten proportionately worse for everyone,” said Nat Markus, a senior researcher at the American Enterprise Institute, who collected and studied the data.

Victoria, Texas, reopened schools in August 2020, earlier than many other school districts. Still, student absenteeism in the district doubled.

Kayleigh Greenlee, New York Times

This trend suggests that something fundamental is changing in American childhood and school culture, and that it may last for a long time. The once deeply ingrained habit of waking up in the morning, getting on the bus, and reporting to class is now much more tenuous.

“The relationship with school has become voluntary,” says Katie Rothenbaum, a psychologist and associate research professor at Duke University's Child and Family Policy Center.

The tradition of daily attendance and the trust of many families were severed when schools closed in the spring of 2020. Even after schools reopened, the situation did not return to normal. The district offered remote options, mandated Covid-19 quarantines and relaxed attendance and grading policies.

Student absenteeism is now a major factor hindering the nation's recovery from the learning loss caused by the pandemic, education experts say. Students cannot learn unless they go to school. Also, if a classmate who is absent takes turns appearing, it can have a negative impact on the student's grade, even if the student is present. Because teachers need to slow down and adjust their approach to keep everyone on track.

“If we don't address absenteeism, everything is for naught,” said Mount Diablo Unified, a socio-economically and racially diverse district of 29,000 students in Northern California. Superintendent Adam Clark said the district has seen an “explosion” in absenteeism. Approximately 25% of students. This is up from 12% before the pandemic.

U.S. students as a whole have not made up for losses due to the pandemic. Absenteeism is one of the main reasons.

Kayleigh Greenlee, New York Times

Reasons why students are absent from school

Schools everywhere are scrambling to improve attendance, but the new calculus among families is complex and multifaceted.

At South Anchorage High School in Anchorage, the students are mostly white, middle- to upper-income, and some families go on ski trips during the school year or take advantage of off-peak travel discounts for a two-week vacation in Hawaii. said Sarah Miller, a counselor at the school.

For a small number of students in a school who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, the reasons are different and more difficult. They often have to stay home to care for their younger siblings, Miller said. On days when you miss the bus, your parents may be busy with work or there may not be a car to take you to school.

And because teachers are still expected to post class assignments online, often only skeletal versions of assignments, families mistakenly think their students are keeping up with class. said Miller.

Sarah Miller, a counselor at South Anchorage High School for 20 years, is currently seeing an increase in student absenteeism across the socio-economic spectrum.

Ash Adams of the New York Times

Across the country, students are staying home not just for the coronavirus, but for more common illnesses such as colds and viruses.

And in Mason, Ohio, a wealthy Cincinnati suburb, one reason for the rise in absenteeism is that more students are struggling with mental health issues, said Tracy Carson, a district spokeswoman. Many parents are able to work remotely, allowing their children to stay home as well.

Ashley Cooper, 31, of San Marcos, Texas, said the pandemic shattered her faith in the education system, leaving her daughter learning online with little support and struggling to perform at grade level when she returned home. He said he was expected to make it. She said her daughter fell behind in math and she has been suffering from anxiety ever since.

“There were days when she would be completely in tears — 'I can't do this.' Mom, I don't want to go,” Cooper said. Ms. Cooper has been working with the nonprofit organization School Communities to improve children's school attendance rates. But, she added, “I think as a mother, it's okay to have a mental health day where you say, 'I hear you and I hear you too.'” You matter. '”

Experts say school absences are both a symptom and a cause of pandemic-related challenges. Students who are academically behind may not want to attend, but their absence will cause them to fall further behind. Students with anxiety may avoid school, but hiding can make their anxiety even worse.

Schools have also seen an increase in discipline problems intertwined with absenteeism since the pandemic.

Dr. Rosenbaum, a psychologist at Duke University, says that absenteeism and outbursts are both examples of human stress responses, and that they are currently playing out all at once in schools, such as fighting (verbal and physical aggression) and running away (absenteeism). ).

“If the kids aren't here, you're not building relationships,” said Quintin Shepard, superintendent of schools in Victoria, Texas.

Kayleigh Greenlee, New York Times

Victoria, Texas, Superintendent Quintin Shepard first focused on student behavior after schools reopened in August 2020, describing it as a “kitchen fire.”

The district, which has about 13,000 mostly low-income and Hispanic students, has found success with a one-on-one coaching program that teaches its most disruptive students coping strategies. In some cases, student violence in the classroom has gone from 20 incidents a year to fewer than five, Sheppard said.

However, chronic absenteeism has not yet been overcome. About 30% of students are chronically absent this year, about twice as many as before the pandemic.

Although Dr. Shepherd initially hoped that student absenteeism would improve on its own over time, he begins to believe that it is actually the root of many of the problems.

“If the kids aren't here, you can't build relationships,” he says. “If they're not building relationships, you should expect to have problems with behavior or discipline. If they're not here, they're not going to be able to learn academically and they're going to struggle. If they are struggling in class, expect violent behavior.”

Teacher absenteeism has also increased since the pandemic, and student absences mean uncertainty about which friends and classmates will attend. That could lead to increased absenteeism, said Michael A. Gottfried, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Graduate School of Education. His research shows that if 10 percent of a student's classmates are absent on one day, that student is more likely to be absent the next day.

Classmates who are absent can negatively impact the grades and attendance of students who are present, even if they are present.

Ash Adams of the New York Times

Is this the new normal?

In many ways, the challenges facing schools are those being felt more broadly in American society. Have the cultural changes caused by the pandemic become permanent?

U.S. employees have continued to work from home at a pace that has remained largely unchanged since late 2022. Companies have been able to some extent to “put the genie back in the bottle” by mandating a return to the office several days a day. said Nicholas Bloom, a Stanford University economist who studies remote work. But hybrid office culture is likely to be here to stay, he said.

Some wonder if it's time for schools to become more realistic.

Lakisha Young, chief executive of Oakland REACH, a parent advocacy group that works with low-income families in California, said strict online options are available in emergencies, such as when a student misses a bus or needs care. Proposed. A member of her family. “The goal is: How do we make sure this child gets an education,” she said.

Relationships with adults at school and other classmates are very important for attendance.

Kayleigh Greenlee, New York Times

In the corporate world, companies have found some success in projecting a sense of social responsibility by relying on each other to make sure co-workers show up to work on their appointed days.

Similar dynamics may be at work in schools, where experts say strong relationships are essential for attendance.

There's a sense of, “If I don't show up, will people even miss the fact that I'm not there?” said Charlene M. Russell Tucker, Connecticut State Education Commissioner.

In her state, home visiting programs achieve positive outcomes by working with families to address the specific reasons students are absent from school and by building relationships with caring adults. is bringing. Other efforts, such as sending text messages or postcards to parents informing them of the cumulative number of absences, can also be effective.

Regina Murph has been working to get her sons, ages 6 and 12, back into the daily routine of attending school.

Sylvia Jarrus writes for The New York Times

In the Ann Arbor suburb of Ypsilanti, Michigan, home visits helped Regina Murph, 44, feel less alone as she struggled to get her children to school each morning.

After working in a nursing home during the pandemic and then losing her sister to COVID-19, she said some days she found it difficult to get out of bed. Murph also said she was proactive about keeping her children home when they were sick for fear of accidentally spreading the virus.

But after receiving visits from the school district and starting therapy on her own, she has settled into a new normal. She helps her sons, ages 6 and 12, get their night clothes ready and wakes up at 6 a.m. to make sure her sons catch the bus. She said she knows to make kids miss school if they're sick. “I made a huge transition in my life,” she said.

But creating meaningful change for many students continues to be slow and difficult.

Nationally, about 26% of students were considered chronically absent last school year, up from 15% before the pandemic.

Kayleigh Greenlee, New York Times

The Ypsilanti School District has tried a little bit of everything, Superintendent Alena Zachery-Ross said. In addition to door-knocking, officials are looking for ways to make schools more attractive to the district's 3,800 students, more than 80% of whom qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. They held themed dress-up days, such as 70s Day and Pajama Day, and gave away warm clothing after noticing a drop in attendance during the winter months.

“We wondered: Is it because he's not wearing a coat? Is it because he's not wearing boots?” Dr. Zachery Ross said.

Still, overall absenteeism rates remain higher than before the pandemic. “We don't have the answers yet,” she says.