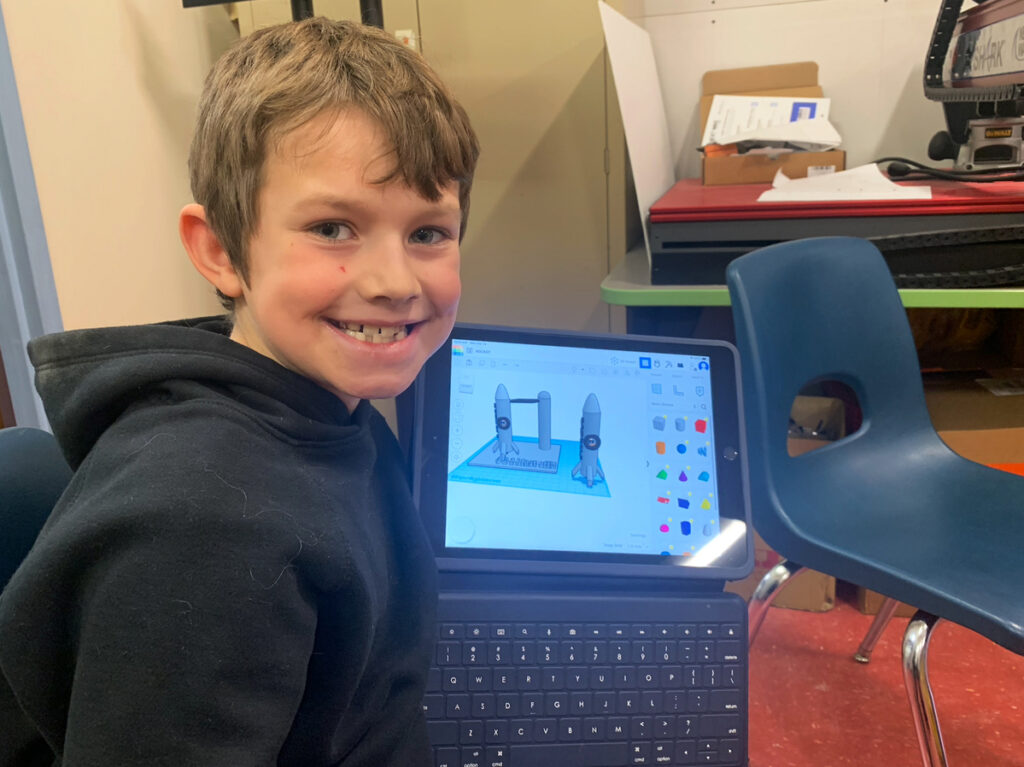

On a recent morning at St. George School in Tennants Harbor, 9-year-old Gilbert Boynton showed off designs he created using a 3D printing app, including rockets, stores and name tags.

Surrounded by 3D printers, laser cutters and school project pieces, Gilbert said he loves building things when he's not playing hockey. In fact, it's his favorite part of school. To demonstrate his skills, he used the app to design a door with a window and doorknob within his 30 seconds.

“Since the beginning of the school year, my goal has been to create,” Gilbert said. “I love making things. I love being quick. I love doing things like this.”

He is in the right position. St. George's School is unique in that it incorporates hands-on learning into every aspect of the education its 200 primary and middle school students receive. The model recently received national attention, winning a prestigious $500,000 prize and being featured in the Wall Street Journal.

It's been nearly 10 years since St. George, a fishing community with many seasonal residents, decided to create a new local school district focused on career and technical education on its own, according to Superintendent Mike Felton. . Now, the school is poised to take that model even further, breaking ground next week on a $3.5 million building to house the makerspace program it originally launched in 2016.

This is part of a larger movement to reinvigorate the vocational training that students receive so that they have a solid career path after graduation. Maine has pushed to expand its career and technical programs in recent years, especially after business declined during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, while much of that education takes place in high school, St. George's School is unique in that it provides education to children who are not old enough to attend the state's vocational schools.

Its $500,000 award, which it recently received from Forbes and the Center for Educational Innovation, was intended to reward its educational innovation and fund the construction of a makerspace building.

The makerspace is currently located in the main school building, and the room is equipped with eight 3D printers, Legos, and other tools that students can use for their projects. However, the space is not large enough to meet the school's goals.

For example, the school has CNC machines, short for computer numerical control, that can perform sophisticated manufacturing tasks based on computer instructions, but the school doesn't have enough space in the rooms to operate them safely. said Paul Minersman of the school. Technology and Makerspace Director.

Felton said the new 5,000-square-foot building will include traditional classroom space, sewing machines, 3D printers, CNC machinery, shipbuilding, woodworking, metal fabrication and other facilities.

The building reflects the fact that technical education is integrated into the entire curriculum at St. George's, rather than being part of a separate class. For example, modeling, architecture and technology fundamentals are woven into other subjects such as math and history, teaching students perseverance and introducing them to trades, Felton said.

“We don't want them on the screen all the time. We want them to be able to use their hands as well as do the digital part,” Felton said.

That was evident to fourth-grade teacher Jaime MacCaffray, who said her students set goals at the beginning of the year and, after learning how to 3D model and code, start designing things themselves.

“[All] All everyone is talking about right now is how difficult it is to get kids to work. And yes, it's true. “It's hard to keep kids engaged, but when they have the opportunity to build something or dig deeper, they become a little more enthusiastic,” McCaffrey said.

McCaffrey said the students will soon be working on a project focused on animal evolution, in which they will design a fictional animal specifically adapted to Maine's climate. Students sew their animals or design them in a 3D modeling and printing app called Tinkercad.

The district had to raise significant funds from the community to construct the new building. One of the residents, Wickham Skinner, a former Harvard professor who worked on the Manhattan Project and died in 2019, helped the school secure grants to pay for much of the technology. Some posters paid thousands of dollars at auction for birdhouses built by first graders.

“I think one of the beauties of this community is that it's essentially a traditional working-class fishing community that has always valued hands-on work,” Felton said.

Engineering is not for everyone, but introducing students to hands-on learning will help them understand their career options before graduation, school officials said. This is whether you attend trade school to become a welder, start an apprenticeship to become an electrician or plumber, or obtain some other level of higher education before moving on to another type of career. This also applies to

“As long as they understand their options and are doing a job they love and can make enough to support themselves and their families, we've done our job,” Felton said.