Despite introspective and earnest efforts from both the German authorities and the general public, antisemitic attitudes and hate crimes make an explosive comeback in the birthplace of ‘genocide’

In a conference room in Fürth, Germany, a group of 20 shuffles in for a workshop entitled “The Jews and cyclists are to blame for everything.” It covers Jewish history, culture, ties to Israel, what antisemitism looks like, where it comes from, and most importantly, how to address it.

But, contrary to expectations, not one person in the workshop—including its lead educator—was Jewish. Many of the participants admitted to The Media Line that they don’t even know any Jews, who comprise fewer than 1% of the German population today.

This is not an isolated incident. Group after group, paid and free, people learn about a minority group they often know nothing about to address a societal ill that seemingly doesn’t affect them.

“For a long time, I didn’t want to offer any antisemitism workshops,” Daniela Eisenstein, Director of the Jewish Museum Franconia in Fürth—which hosts the workshop—told The Media Line. “I believe our primary mission is to convey Jewish life and history,” as opposed to antisemitism.

But the rising demand for the lessons changed her mind.

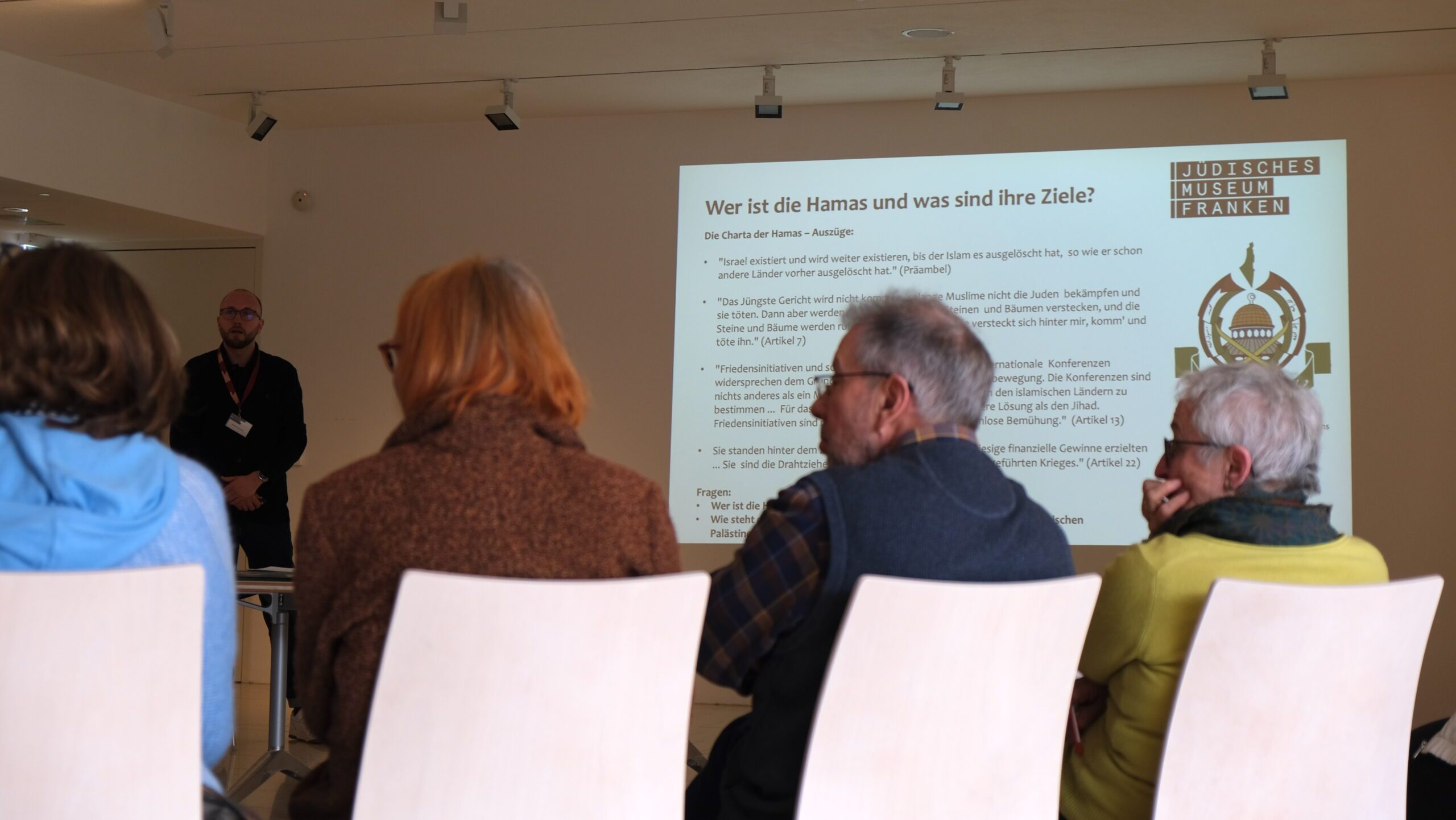

Ben Herrmann of the Education Department at the Jewish Museum Franconia in Fürth discusses addresses participants at the antisemitism workshop. The slide in the background reads “When is criticism of Israel antisemitism?” March 16, 2024 (Aaron Poris)

According to Eisenstein, many teachers and non-Jews, long before Oct. 7, 2023, contacted the organization. She noted that many asked, “‘Can you please offer something on antisemitism? We’re dealing with it with our colleagues or students in class, and we don’t know how to react.’”

“We started working on a concept for teachers and schoolchildren. … It took about three years before it was finally ready to offer.”

Today, the workshop is requested by educators, law enforcement, and the average German Joe.

Concerns about antisemitism in Germany have been rising for years—reaching a fever pitch after a series of recent events across the country, including home invasions, attacks on the street, and threats against synagogues and Jewish businesses not seen since the 1930s.

“My question is, ‘How can I deal rationally with people who are thinking irrationally?’” workshop participant Romy, who preferred not to give her last name, told The Media Line.

“What can I say if someone comes to me and says some antisemitic nonsense? I have no answer yet,” Judith Kleinemas, another workshop participant, said to The Media Line.

Attendee David Micolay agreed, adding, “I always like to learn more about the state of Israel and efforts to make peace.”

“I’m interested in what happened in the past, and I wanted more information,” Maria Schwager noted.

And with that, a strange tale of two very different Germanys emerges.

In the first, what we’ll call “Germany A,” the government’s position—as consistently laid out by the likes of President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck, and many others in the Bundestag (Germany’s parliament)—suggests outright support for Israel’s mission to eradicate Hamas from its borders, provided Israel does more to support innocent Palestinians caught in the crossfire.

Participants at the antisemitism workshop at the Jewish Museum Franconia in Fürth, Germany. The slide in the background reads “Who is Hamas and what are their goals?” (Aaron Poris)

Scholz visited Israel three times since the October 7 attacks alone, including most recently on March 17, where he and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu discussed the need for increasing humanitarian aid to Gaza.

“We cannot stand by and watch the Palestinians starve. Terrorism cannot be stopped by military means alone. … We believe the introduction of humanitarian aid and its distribution within the Strip should be improved,” Scholz said.

In Germany A, Vice Chancellor Habeck issued a 10-minute statement in early November—translated into English, Hebrew, and Arabic—about the need to address antisemitism within one’s own communities, the “unacceptable Islamist demonstrations” that have cropped up in Berlin and elsewhere, and everyone’s equal rights to protection under the law.

In Germany A, citizens of all ages and from all walks of life display incredible introspection and desire to learn more about addressing hate in their communities.

However, on the other side, in “Germany B,” Jews have visibly become less visible. They know they may be targeted anywhere and anytime. They’ve stopped wearing identifying Jewelry and clothing. They’ve stopped speaking Hebrew in public or engaging in discussions about Israel or Gaza.

The large majority of people reject explicit and easily identifiable antisemitism, according to nearly every study and poll.

Additionally, where attitudes related to the Israel-Palestinian conflict are concerned, the October 7 attacks shifted public opinion in Germany towards blaming Palestinians more for the lack of peace in the region, according to a YouGov Eurotrack poll updated in December 2023.

But while overt antisemitism is rejected, support for antisemitic sentiments and beliefs is where things get trickier.

Antisemitism has been increasing globally among both extreme left and right-wing groups for years, particularly under the influence of conspiracies tied to Jews’ and Israel’s influence over economic markets, politics, media, and even the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 2023 Anti-Defamation League (ADL) Global 100 Antisemitism Index found that roughly 25% of European residents harbored harmful antisemitic attitudes—rising to 34% in Western European countries like Poland and Hungary.

In Germany, this number falls to 12% of the adult population.

But that’s nearly 8.5 million people who hold negative attitudes towards Jews, who, by comparison, comprise just 120,000 people—fewer than 1% of the total German population.

This doesn’t mean that the other 87% of Germany is problem-free.

The ADL reports that 44% of Germans think Jews are more loyal to Israel than their home/host nations, 21% believe Jews exercise too much power in the international economic markets, 13% think Jews have too much control over global media, and 30% “hate Jews because of the way Jews behave.”

And these attitudes translate into very real attacks.

According to the Bundestag’s own Research and Information on Antisemitism (RIAS) report, antisemitic attacks have exploded by over 320% in just the first thirty days after Oct. 7, emboldened by the Israel-Hamas conflict. Attacks have risen to an average of 29 incidents per day compared to 7 per day in 2022.

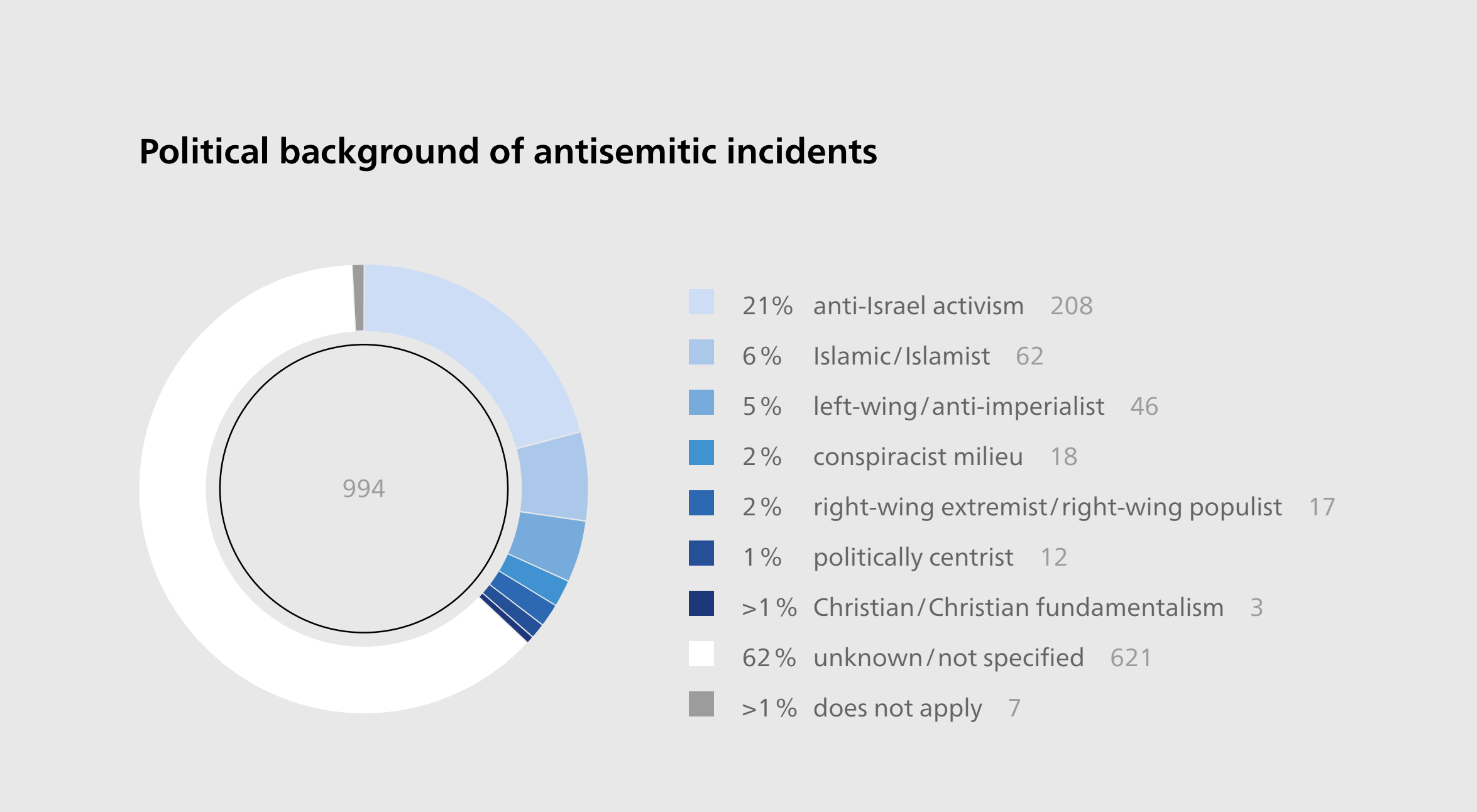

To put that in real numbers, that’s 994 verified antisemitic incidents in Germany between October 7 and November 9, 2023—697 of which were in public locations, on public transportation, or in schools—including three cases of extreme violence, 29 assaults, 72 cases of targeted damage to property, 32 threats, and 854 cases of abusive behavior.

Where motives could be determined, 21% were attributed to anti-Israel activism, 6% to Islamic extremism, 5% to left-wing anti-imperialist ideologies, and 2% to right-wing extremism and conspiracies.

A graph showing the known political background of perpetrators of antisemitic incidents committed in Germany between October 7 and November 9, 2023. (RIAS Berlin Report)

On Oct. 17 in Hesse, an Israeli man “was aggressively asked by two men at his front door to remove the Israeli flag he had hung on his balcony. When he refused, they insulted him in an antisemitic manner. As he attempted to inform the police, they snatched his cell phone and gained access to his apartment. The men took the Israeli flag and hit the man in the face with their fists,” the RIAS report reads.

The next day in Berlin, “two incendiary devices were thrown at a Jewish community center, which houses a synagogue, a school, and a daycare center,” the report continues.

“We are living in a constantly ‘interesting’ situation,” says Jo-Achim Hamburger, chairman of the Jewish Community Center in Nürnberg, speaking to The Media Line. “You saw the fences, the cameras, the doors, the bulletproofing… We have police standing outside the doors during services. We’re building a kindergarten with bulletproof windows. It’s not normal.”

But especially threatening are cases where Jewish residences and businesses are marked with stars of David and swastikas, “reminiscent of the practice under National Socialism,” the RIAS report reads.

“Marking people’s houses and things, that’s frightening,” Romy said, “not only to me but for society.”

“I told my son not to make a big issue out of being Jewish at the moment and to avoid talks about the Middle East because I’m afraid he will get beaten up at school where he’s the only Jewish student,” adds Eisenstein, who explains that it pains her to speak this way—especially as the head of a Jewish museum.

Where Does It Come From?

When discussing antisemitism’s “comeback,” many argue it never went away.

“The Nazis didn’t die out after WWII,” Hamburger said. “They were in politics, in the police… Only in the last quarter century did people really try to work on their past. Everyone seems to think their family fought the Nazis. Fairy-tales. Lies.”

Even Hamburger’s family home was fitted with bulletproofing and security measures similar to those of the community center due to the threats levied against his father, Arno Hamburger—the previous chairman of the community. “We’ve been growing up with this since the 60s,” he explained.

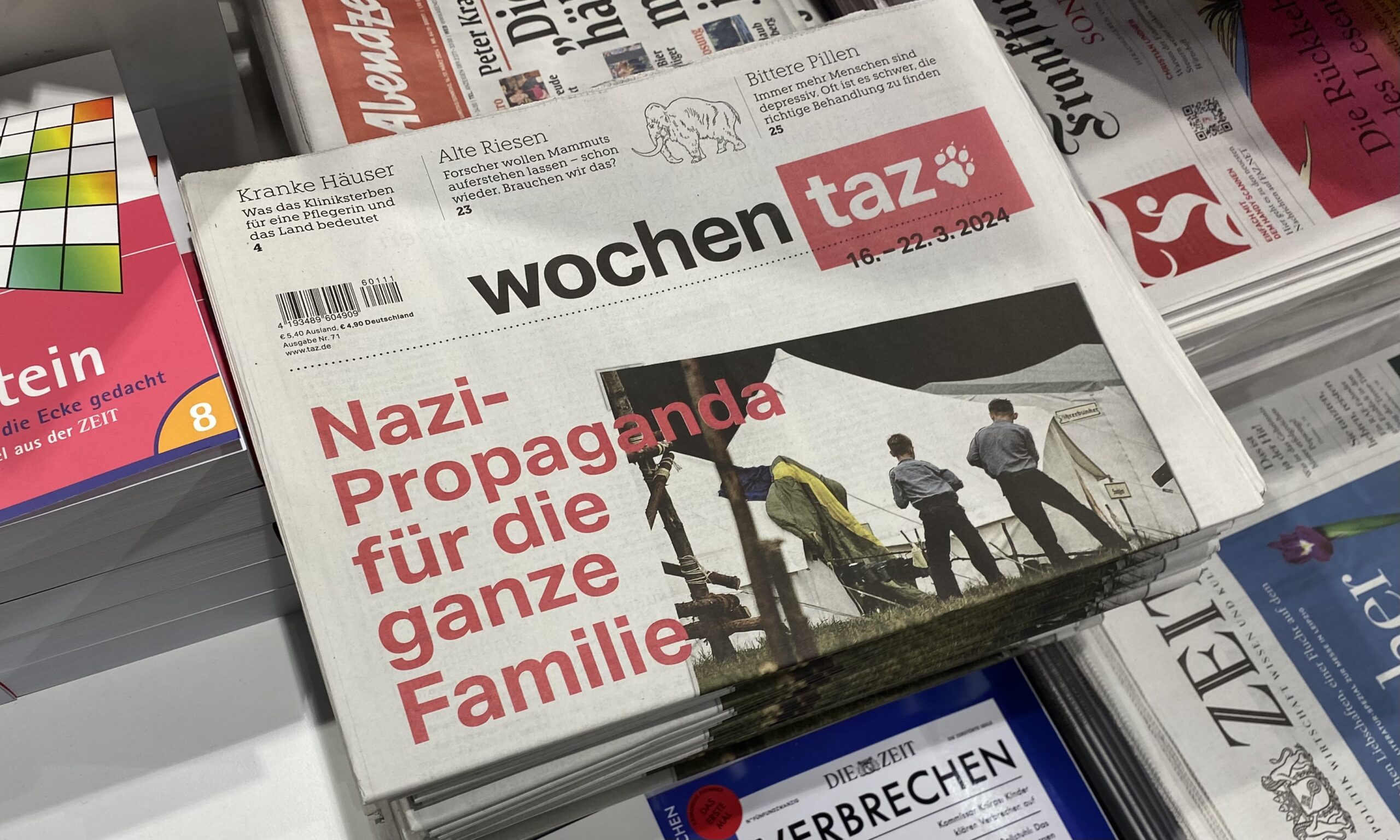

And, walking into a bookstore at the train station, one can see that Hamburger’s allegations are confirmed. The front page of the German newspaper Wochen Taz reads “Nazi Propaganda for the Whole Family” and tells of a generations-long campaign to indoctrinate thousands of youths across Germany into the Nationalist Socialist ideology.

Germany’s Wochen Taz newspaper for the week of March 16-22, 2024. The headline story reads “Nazi Propaganda for the Whole Family,” March 17, 2024 (Aaron Poris)

The ADL’s Global 100 report also shows that the rates of antisemitic views increase proportionally with age, with 6% of German adults 18-34 holding such views versus 16% of those over 50.

Meanwhile, the Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS) research group reports support for antisemitic attitudes primarily among people with low levels of formal education and with the right-wing Alternative for Deutschland Party—but also with the politically extreme-left, Muslims, and immigrants.

An estimated 300,000 Palestinians are living in Germany today, and close to 6 million Muslims, with as many as 50% of them reportedly viewing Jews unfavorably.

However, speaking to The Media Line at a pro-Palestinian demonstration in Nürnberg, Wassim Hayek of the Palemanya protest group disagreed.

Hayek, a German of Lebanese descent, says, “At the start of the war, we weren’t being heard. So, everything we spoke about was turned into the idea that we were against Jews. But it’s not about religion.”

“Our problem is with the Israeli government. We are against the war. Our target is to all live in harmony together.”

Hayek went on to say he agrees that Hamas is part of the problem and that he prays for peace in the Middle East between all nations, including Israel. But he wants Germany to value Palestinian lives in Gaza and to pressure Israel more about its war efforts.

Asked about how Jews feel under attack in Germany, he adds, “Of course, there are incidents where Muslims target Jews and where Jews target Muslims. … You will always have religious extremists on both sides, and we will always have to fight extremism. But generally, I don’t think there is a problem between the religions.”

Indeed, the ADL reports that some 15% of Germans harbor unfavorable opinions of Muslims as well, with some 258 Islamophobic crimes, including attacks on mosques and individuals reported by the German police in the first half of 2023, and another 53 cases of anti-Muslim threats and violence documented by the Berlin-based rights group CLAIM between October 7 and November 24, 2023.

Pro-Palestinian activists attend the Palemanya protest group’s “Die-In” in downtown Nürnberg, Germany, March 15, 2024. (Aaron Poris)

Mohammad [last name withheld], an immigrant from Egypt, tells The Media Line a similar story. He’s against all wars and says it warms his heart to see people passionate about helping warms his heart others. He even proudly presented a commendation letter from the hospital where he works, describing how he prevented a violent attack between patients. But he laments the loneliness he experiences in his new homeland.

The majority of antisemitic tendencies, then, seem to increase online and on social media platforms like TikTok, which prioritize conflict and lack context.

“The greatest problem is how people get their information,” Eisenstein agrees. And in speaking with Germans on the street—none of whom wanted to be identified in this article—those who said they got their news from social media tended to say that Israel-Gaza was the most concerning conflict in their opinion, more so than the Russian invasion of Ukraine or the EU Farming protests. Yet they also tended to know the least about the conflict, its actors, their motivations, etc.

Several suggested Germany’s strong stance with Israel was motivated by economic interests and guilt about the Holocaust and WWII.

What’s Next?

Most say, however, that the authorities and political class in Germany thankfully seem most resistant to antisemitic and bigoted attitudes.

Former Israeli Ambassador to Israel, Jeremy Issacharoff, tells The Media Line that you can see as much in the government’s response to the war and that the leadership “has been first class in terms of support.”

“Does Germany feel guilty about the Holocaust? Yes,” Issacharoff continues, but that’s not enough to sustain relations, he says. He also noted that the relationship with Germany is probably Israel’s “most strategic partnership” in Europe.

Meanwhile, as seen above, there is growing interest among the general public in learning more.

“More people support Israel because they think the case is just and that the terror wouldn’t stop with the Jews,” says Hamburger.

But far more inter-community outreach is necessary. Asked where he sees the future of the German Jews, Hamburger says, “Sometimes I ask myself the same question, but I have hopes in the youth that someday they’ll find a life that is integrated into normal German society and life.”

However, he thinks reaching this goal will take several generations from now.