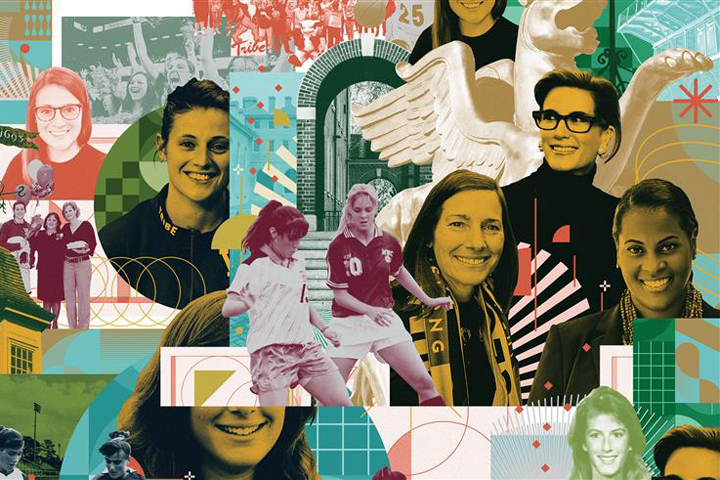

The following excerpt is from an article originally published in the Winter 2024 issue of W&M Alumni Magazine. Please see the full version on the magazine website. – Ed.

Participation in sports provides a solid foundation for women who aspire to high-level leadership roles. According to the EY report, 94% of women in so-called executive roles, such as chief executive officer, chief operating officer, and chief financial officer, are former athletes, and 52% of them played at the collegiate level. He says he has experience. The report states that time spent on the field or court develops a strong work ethic, determination, commitment to teamwork and competitive spirit.

Athletics helps level the playing field for women in the business environment. A United Nations report on women and gender equality notes that “women in sports leadership can shape attitudes toward women's abilities as leaders and decision-makers, especially in traditionally male domains.” are doing.

To learn more about the relationship between athletic performance and leadership in the workplace, we spoke to several William & Mary alumni who have transitioned from athletes to corporate and nonprofit executives. To learn more about alumni holding positions of power in the business and nonprofit sectors, visit magazine.wm.edu/womenathletes.

Mashea Mason Ashton '96, MAEd. '97

At Digital Pioneers Academy in Southeast Washington, D.C., the school's founder and CEO, Mashea Ashton, is wearing his usual Wednesday attire: a green and gold William & Mary sweatshirt. After all, Wednesday is college day. Why wouldn't a former Tribal soccer team captain represent her beloved alma mater?

The mission of public charter schools is to prepare students from low-income, working-class families to attend college and pursue careers in computer science. Since opening in 2018 with 120 sixth grade students, the academy has grown to include two campuses and 600 students from 6th grade through 11th grade. did. The first batch of students will graduate next year.

“We believe every student will reach the level you expect,” Ashton says. “However, data shows that educational outcomes for children of color, especially those living in some of the most under-resourced areas of the country, remain far below their potential.” The big question is: How can we encourage more children of color to reach their full potential by going to college and having successful careers?”

The issue first came into focus when Ashton was teaching in Williamsburg, pursuing a master's degree in special education after earning a bachelor's degree in sociology and elementary education. One of her students was a male student in her fifth grade who was getting into trouble for his behavior. A staff teacher at the school told Mr Ashton not to worry: “He'll just end up in prison like his father.”

“I remember thinking, 'Oh my god, this can't be true.' There must be something else to him,” Ashton says.

The story of how she came to attend William & Mary and discover her life's calling begins with athletics. As soon as Machere and her twin sister Michelle Mason '96 entered kindergarten, her mother, Brenda Mason, began making plans for the girls to attend college. Although she did not have a degree as both she and her husband were in the military, it was her dream to see her daughters receive higher education.

While volunteering in the Willingboro, New Jersey, school system, Mrs. Mason told one of the teachers that her daughters needed to receive scholarships and that the best way to achieve that goal was to excel at basketball. He said that he thought this might be a method.

“This teacher told my mom, 'Don't put your kids in basketball, put them in soccer,'” Ashton said. “I think the idea was that there weren't many black girls playing soccer. If they were really good, they would stand out and have a better chance of getting a scholarship.”

So the twins started playing club soccer at the age of five and loved it. About 10 years later, their team, the Willingboro Strikers, became the national champions of his under-16 group. Growing up in southern New Jersey, William and Mary didn't deserve the attention they deserved, but at a Women's and Girls in Soccer tournament, they met then-W&M women's soccer head coach John Daly. He told his mother that the girls should consider going. To William and Mary. His suggestion was further strengthened when he heard from one of the club's soccer coaches, whose children attended the university, about W&M's reputation for both high-level academics and athletic talent.

“We said, 'This is our dream school,' and that's where we want to go,” Ashton says. “It's the only school we applied to.”

She believes her experience as an athlete has honed her leadership skills and taught her how to overcome disappointments and setbacks. She recalls that after starting most games as a freshman, she lost her spot in the lineup when new players came in the following year.

“Why do freshmen get the starting spot?” Ashton asked Daly. He told her he made the decision after evaluating how her player skills would contribute to the team's success and encouraged her to continue to grow as an athlete.

“Competition forces me to work harder,” she says. “I started as early as my junior year. My senior year, I was elected captain. A big part of that was the input from my coach. He emphasized that if you work hard, good things will happen. .”

As she began her career in education, she carried with her the competitive spirit and lessons of resilience from her soccer team.

“From an athletics perspective, I understand that you work hard and get results, but the same perspective applies to anything,” she says. “If you aim big, work hard, persevere, and believe that all failures and difficulties are just feedback, you can achieve anything.”

Ashton started as a classroom teacher and quickly moved into a leadership role. At age 26, she became a founding member of the Black Alliance for Education Options, a nonprofit organization that advocates for increased options for low-income and working-class families. She served on the board along with U.S. Sen. Cory Booker, then the mayor of Newark, New Jersey. Mr. Booker later hired her as CEO of a $50 million fund set aside for charter schools in Newark. Ashton also served as Executive Director of the New York City Department of Education's Charter Schools and Director of National Recruitment for the Knowledge Is Power program.

“I didn’t choose charter school,” she says. “I chose leadership roles based on how I can influence children to serve them.”

The idea of charter schools resonated with her partly because of personal experience. Her parents had transferred Mashea and Michele from a designated public school, saying it would prevent them from repeating kindergarten. They transferred to a private Catholic school where they received additional academic support and were able to catch up with their classmates.

“I think families should have as many quality options as possible,” she says.

Working with charter schools allowed Mashare to apply an entrepreneurial approach to education, which ultimately led to the creation of Digital Pioneer Academy (DPA). About 10 years ago, she and her husband, Kendrick Ashton '98, moved from New York City to the Washington, D.C., area, where his family has lived for generations, as they planned to start the St. James Sports Complex. I emigrated. Friend and business partner Craig Dixon, ’97, JD, ’00;

Ms. Mashare has reconnected with her alma mater as the current director of the W&M Foundation. in bold DC Regional Campaign Director and W&M Alumni Association Director.

Originally, she wanted to open a middle school that would put students on the path to college and employment. She then read a report stating that the demand for people trained in the computer sciences was expected to far outstrip the supply, and was inspired to found the academy.

“I said, 'Let's figure out a way to close this gap,'” Ashton says. “We want academics to participate in creation in the digital economy.”

Taking a school from conception to opening is a major undertaking, and challenges continue. Ashton began rethinking how DPA operates after four Academy students were killed in gun violence during an off-campus incident last school year.

“What I'm realizing is that if we don't also think thoughtfully about addressing youth violence and gun violence, all these kids are going to go to four-year colleges and succeed in their 21st century careers. “It means we can't accomplish our mission. DC,” she says.

As part of the school's response, it started a football team, which completed its first season this fall. Sports such as women's volleyball, men's volleyball, basketball, and soccer have also been added. These activities give students something to do after school, a way to engage with families, and build a sense of community.

Meanwhile, Ashton keeps the team focused on the Digital Pioneer Academy's mission by leveraging his athletics background.

“We have a 15-minute huddle with all of our staff at the beginning of each day. It's our team's favorite moment,” she says. “We talk about how we played that day and then we try to win. Our mindset is we have to go 1-0 every day. We're not trying to win a championship in one day. No. We are taking it one day at a time.”

Read the full story, including Molly Ashby ’81, Katie Newmar ’07, and Jennifer “Jen” Tepper Mackesy ’91, on the magazine’s website.

Tina Eshlman, University Marketing