By Jean MackenzieSeoul correspondent

Jean Chung

Jean ChungOn a rainy Tuesday afternoon, Yejin is cooking lunch for her friends at her apartment, where she lives alone on the outskirts of Seoul, happily single.

While they eat, one of them pulls up a well-worn meme of a cartoon dinosaur on her phone. “Be careful,” the dinosaur says. “Don’t let yourself become extinct like us”.

The women all laugh.

“It’s funny, but it’s dark, because we know we could be causing our own extinction,” says Yejin, a 30-year-old television producer.

Neither she, nor any of her friends, are planning on having children. They are part of a growing community of women choosing the child-free life.

South Korea has the lowest birth rate in the world, and it continues to plummet, beating its own staggeringly low record year after year.

Figures released on Wednesday show it fell by another 8% in 2023 to 0.72. Seoul’s birth rate has sunk to 0.55 – the lowest in the country.

This refers to the number of children a woman is expected to have in her lifetime. For a population to hold steady, that number should be 2.1.

If this trend continues, Korea’s population is estimated to halve by the year 2100.

A ‘national emergency’

Globally, developed countries are seeing birth rates fall, but none in such an extreme way as South Korea.

Its projections are grim.

In 50 years time, the number of working age people will have halved, the pool eligible to take part in the country’s mandatory military service will have shrunk by 58%, and nearly half the population will be older than 65.

This bodes so badly for the country’s economy, pension pot, and security that politicians have declared it “a national emergency”.

For nearly 20 years, successive governments have thrown money at the problem – 379.8 trillion KRW ($286bn; £226bn) to be exact.

Couples who have children are showered with cash, from monthly handouts to subsidised housing and free taxis. Hospital bills and even IVF treatments are covered, though only for those who are married.

Such financial incentives have not worked, leading politicians to brainstorm more “creative” solutions, like hiring nannies from South East Asia and paying them below minimum wage, and exempting men from serving in the military service if they have three children before turning 30.

Unsurprisingly, policymakers have been accused of not listening to young people – especially women – about their needs. And so, over the past year we have travelled around the country, speaking to women to understand the reasons behind their decision not to have children.

Jean Chung

Jean ChungWhen Yejin decided to live alone in her mid-20s, she defied social norms – in Korea, single living is largely considered a temporary phase in one’s life.

Then five years ago, she decided not to get married, and not to have children.

“It’s hard to find a dateable man in Korea – one who will share the chores and the childcare equally,” she tells me, “And women who have babies alone are not judged kindly.”

In 2022, only 2% of births in South Korea occurred outside of marriage.

‘A perpetual cycle of work’

Instead, Yejin has chosen to focus on her career in television, which, she argues, doesn’t allow her enough time to raise a child anyway. Korean work hours are notoriously long.

Yejin works a traditional 9-6 job (the Korean equivalent of a 9-5) but says she usually doesn’t leave the office until 8pm and there is overtime on top of that. Once she gets home, she only has time to clean the house or exercise before bed.

“I love my job, it brings me so much fulfilment,” she says. “But working in Korea is hard, you’re stuck in a perpetual cycle of work.”

Yejin says there is also pressure to study in her spare time, to get better at her job: “Koreans have this mindset that if you don’t continuously work on self-improvement, you’re going to get left behind, and become a failure. This fear makes us work twice as hard.”

“Sometimes at the weekends I go and get an IV drip, just to get enough energy to go back to work on Monday,” she adds casually, as if this were a fairly normal weekend activity.

She also shares the same fear of every woman I spoke to – that if she were to take time off to have a child, she might not be able to return to work.

“There is an implicit pressure from companies that when we have children, we must leave our jobs,” she says. She has watched it happen to her sister and her two favourite news presenters.

‘I know too much’

One 28-year-old woman, who worked in HR, said she’d seen people who were forced to leave their jobs or who were passed over for promotions after taking maternity leave, which had been enough to convince her never to have a baby.

Both men and women are entitled to a year’s leave during the first eight years of their child’s life. But in 2022, only 7% of new fathers used some of their leave, compared to 70% of new mothers.

Jean Chung

Jean ChungKorean women are the most highly educated of those in OECD countries, and yet the country has the worst gender pay gap and a higher-than-average proportion of women out of work compared to men.

Researchers say this proves they are being presented with a trade-off – have a career or have a family. Increasingly, they are choosing a career.

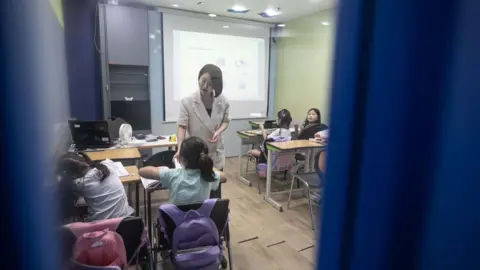

I met Stella Shin at an afterschool club, where she teaches five-year-olds English.

“Look at the children. They’re so cute,” she cooed. But at 39, Stella does not have children of her own. It was not an active decision, she says.

She has been married for six years, and both she and her husband wanted a child but were so busy working and enjoying themselves that time slipped away. Now she has accepted that her lifestyle makes it “impossible”.

“Mothers need to quit work to look after their child full time for the first two years, and this would make me very depressed,” she said. “I love my career and taking care of myself.”

In her spare time Stella attends K-pop dance classes with a group of older women.

This expectation that women take two to three years off work when they have a child is common among women. When I asked Stella whether she could share the parental leave with her husband, she dismissed me with a look.

“It’s like when I make him do the dishes and he always misses a bit, I couldn’t rely on him,” she said.

Even if she wanted to give up work, or juggle a family and a career, she said she could not afford to because the cost of housing is too high.

Jean Chung

Jean ChungMore than half the population live in or around the capital Seoul, which is where the vast majority of opportunities are, creating huge pressure on apartments and resources. Stella and her husband have been gradually pushed further and further away from the capital, into neighbouring provinces, and are still unable to buy their own place.

Seoul’s birth rate has sunk to 0.59 – the lowest in the country.

Housing aside, there is the cost of private education.

From the age of four, children are sent to an array of expensive extra-curricular classes – from maths and English, to music and Taekwondo.

The practice is so widespread that to opt out is seen as setting your child up to fail, an inconceivable notion in hyper-competitive Korea. This has made it the most expensive country in the world to raise a child.

A 2022 study found that only 2% of parents did not pay for private tuition, while 94% said it was a financial burden.

As a teacher at one of these cram schools, Stella understands the burden all too well. She watches parents spend up to £700 ($890) per child a month, many of whom cannot afford it.

“But without these classes, the children fall behind,” she said. “When I’m around the children, I want to have one, but I know too much.”

Jean Chung

Jean ChungFor some, this system of excessive private tuition cuts deeper than cost.

“Minji” wanted to share her experience, but not publicly. She is not ready for her parents to know she will not be having children. “They will be so shocked and disappointed,” she said, from the coastal city of Busan, where she lives with her husband.

Minji confided that her childhood and 20s had been unhappy.

“I’ve spent my whole life studying,” she said – first to get into a good university, then for her civil servant exams, and then to get her first job at 28.

She remembers her childhood years spent in classrooms until late at night, cramming maths, which she loathed and was bad at, while she dreamed of being an artist.

“I’ve had to compete endlessly, not to achieve my dreams, but just to live a mediocre life,” she said. “It’s been so draining.”

Only now, aged 32, does Minji feel free, and able to enjoy herself. She loves to travel and is learning to dive.

But her biggest consideration is that she does not want to put a child through the same competitive misery she experienced.

“Korea is not a place where children can live happily,” she has concluded. Her husband would like a child, and they used to fight about it constantly, but he has come to accept her wishes. Occasionally her heart wavers, she admits, but then she remembers why it cannot be.

A depressing social phenomenon

Over in the city of Daejon, Jungyeon Chun, is in what she calls a “single-parenting marriage”. After picking up her seven-year-old daughter and four-year-old son from school, she tours the nearby playgrounds, passing the hours until her husband returns from work. He rarely makes it home by bedtime.

“I didn’t feel like I was making a major decision having children, I thought I would be able to return to work pretty quickly,” she said.

But soon the social and financial pressures kicked in, and to her surprise she found herself parenting alone. Her husband, a trade unionist, did not help with the childcare or the housework.

“I felt so angry,” she said. “I had been well-educated and taught that women were equal, so I could not accept this.”

Jean Chung

Jean ChungThis sits at the heart of the problem.

Over the past 50 years, Korea’s economy has developed at break-neck speed, propelling women into higher education and the workforce, and expanding their ambitions, but the roles of wife and mother have not evolved at nearly the same pace.

Frustrated, Jungyeon began to observe other mothers. “I was like, ‘Oh, my friend who’s raising a child is also depressed and my friend across the street is depressed too’ and I was like, ‘Oh, this is a social phenomenon’.”

Jean Chung

Jean ChungShe began to doodle her experiences and post them online. “The stories were pouring out of me,” she said. Her webtoon became a huge success, as women across the country related to her work, and Jungyeon is now the author of three published comic books.

Now she says she is past the stage of anger and regret. “I just wish I’d known more about the reality of raising kids, and how much mothers are expected to do,” she said. “The reason women are not having children now is because they have the courage to talk about it.”

But Jungyeon is sad, she says, that women are being denied the wonder of motherhood, because of the “tragic situation they will be forced into”.

But Minji says she is grateful she has agency. “We are the first generation who get to choose. Before it was a given, we had to have children. And so we choose not to because we can.”

‘I’d have 10 children if I could’

Back at Yejin’s apartment, after lunch, her friends are haggling over her books and other belongings.

Fatigued with life in Korea, Yejin has decided to leave for New Zealand. She woke up one morning with a lightbulb realisation that no-one was forcing her to live here.

She researched which countries ranked highly on gender equality, and New Zealand emerged a clear winner. “It’s a place where men and women are paid equally,” she says, almost disbelievingly, “So I’m off.”

I ask Yejin and her friends what, if anything, could convince them to change their minds.

Minsung’s answer surprises me. “I’d love to have children. I’d have 10 if I could,” So, what’s stopping her, I ask? The 27-year-old tells me she is bisexual and has a same-sex partner.

Jean Chung

Jean ChungSame-sex marriage is illegal in South Korea, and unmarried women are not generally permitted to use sperm donors to conceive.

“Hopefully one day this will change, and I’ll be able to marry and have children with the person I love,” she says.

The friends point out the irony, given Korea’s precarious demographic situation, that some women who want to be mothers are not allowed to be.

But it appears politicians might slowly be accepting the depth and complexity of the crisis.

This month, South Korea’s President Yoon Suk Yeol acknowledged that the attempts to spend their way out of the problem “hadn’t worked”, and that South Korea was “excessively and unnecessarily competitive”.

He said his government would now treat the low birth rate as a “structural problem” – though how this will translate into policy is still to be seen.

Earlier this month, I caught up with Yejin from New Zealand, where she had been living for three months.

She was buzzing about her new life and friends, and her job working in the kitchen of a pub. “My work-life balance is so much better,” she said. She can arrange to meet her friends during the week.

“I feel so much more respected at work and people are less judgemental,” she added.

“It’s making me not want to go home.”

Additional reporting by Leehyun Choi and Hosu Lee